Ten years, 1,000,000 hits, and a book later!

Just about ten years ago, when this blog was in its infancy, I garnered some attention by counting down the 100 best film noir posters in a series of weekly posts. When all was said and done, the countdown had been featured on more than 100 different web sites worldwide, attracted more than a million hits, and ultimately led to a book from Fantagraphics, released in 2014. The book features an introduction by none other than William Friedkin, Oscar-winning director of The French Connection and The Exorcist — who says blogging isn’t worthwhile? No longer in print, Film Noir 101 has become a way-too-expensive collector’s item. If you are desperate for a copy, reach out to me. Click on the cover at the right to check it out.

At any rate, I’ve been very lucky to turn a blogging passion into a productive and ongoing relationship with a world-class publisher, not to mention the many opportunities this has created with the great people in the film noir community. I don’t get to dedicate very much time to blogging anymore—I’ve since released another book with Fantagraphics and am finishing up a third, but I still love doing this when I can and will certainly maintain this site forever.

To commemorate the anniversary of the poster countdown, I’ve decided put up this updated version, with revised commentary (my writing back then was even more atrocious than it is now, ugh!) and many improved images.

Here’s how this all started: This was a countdown about graphic design first and foremost. This is a ranking of posters, not movies. In the real world I’m a graphic design professor (as well as Chair of the Department of Art + Design at my school) and a designer who has completed more than 2,000 professional projects. My designs have appeared in what the industry refer to as “the annuals,” (such as Print, How, and Graphis) more than 300 times. I’ve organized numerous gallery exhibitions of film noir posters, including a couple with the Czar of Noir himself, Eddie Muller! I decided it made a ton of sense to do some sort of a countdown that would blend my love of movies with my life as a designer and educator.

What’s eligible:

- Only classic period films were considered (nothing after 1960), though my definition of film noir was much looser for this exercise than it is in than in my writing.

- Only American issue posters of American films were considered. I love European noir posters, but including them would have created an apples and oranges situation.

- Only standard one-sheets were considered. (No half-sheets, 3 or 4 sheets, lobby cards, inserts, daybills, etc.)

- No re-release, reprints, or retrospective posters allowed. Only original, first-run, theatrical release posters.

Judging criteria (In order of prominence):

- Design / Artistic merit. Composition, color, balance, typography, use of illustration or photography, graphic power, etc.

- Concept. How well does the poster communicate the film’s message? Does it tell the truth or is it misleading? Does it connect with the intended audience?

- Originality / Novelty. I reward artistic risk-takers!

- The Blank Slate rule. All films are equal. Double Indemnity doesn’t get a bump for being Double Indemnity. As a matter of fact, that pink monstrosity doesn’t even make the list! In all likelihood, many readers will not have heard of all films on the list, and many will be seeing the posters for the first time. That should be half the fun.

- My personal taste. The least significant of the criteria. My choices are guided primarily by the above, though it would absurd to imagine my personal likes, dislikes, emotions, and sense of nostalgia didn’t play some part in my choices. However I’m not hiding behind personal opinion: this is not a list of my favorites. This is an empirical list of what I consider to be the best, with my personal likes and dislikes shoved as far to the side as possible. And while any such list is, of course, purely opinion, not all opinions carry equal weight: this one is highly educated, professionally seasoned, and exercised daily!

100. The Blue Dahlia (1946)

100. The Blue Dahlia (1946)

Here’s a poster that would certainly have been placed higher (it’s essentially the cover of my book, for Pete’s sake!) were it not so crowded, but I like opening with such a well-known film. As we go through the countdown we’ll see numerous examples of posters designed in the style of mass-market paperbacks by famous authors, meaning that the names of the stars are more important than the title of the picture, and have been placed more prominently in the design. Don’t forget that motion picture marketing relies on star power. Yet this poster could have been executed better. It’s still attractive, but nearly as generic: these three mug shots could have been pulled from any Ladd / Lake / Bendix vehicle. Here’s a movie with a flower in the title, so why not work that motif into the poster, or perhaps include the neon “Blue Dahlia” sign we see in the film? Give me a more precise reference to the content of the movie and I’ll give this a higher ranking.

So why is this poster included when so many hundreds of others were not? The rendering is superb, even if the names at the top seem crammed into the available space. The representations of Ladd and Lake (though less so) are iconic, and the cigarette smoke that cleverly draws the viewer’s eyes across Veronica’s breasts is the icing on the cake. Too bad big Bill Bendix is sporting lipstick, and Doris Dowling (of Bitter Rice fame) is positioned so clumsily — though I’ll admit that her shoe poking through the title typography is a nice touch.

99. The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945)

99. The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945)

Some of Hollywood’s most striking faces don’t translate particularly well to posters, while others become even more beautiful. Ella Raines is one of the unfortunates — take a look at her posters and you’ll realize that art doesn’t imitate life. (Lizabeth Scott, on the other hand, shines in her posters like no other actress.) This example is one of the rare exceptions, as the artist has done a fine job of capturing Raines’s astonishing good looks. An equally fine job has been done with George Sanders.

This poster scores points for not only the quality of the illustration, but also for the striking way in which Sanders’s direct gaze pleads with viewers. I appreciate the strong diagonal composition, but wish the female figure at the top didn’t seem so awkwardly perched atop Sanders’s head.

Finally, notice the ends of the stars’ names along the right-hand edge; draw an imaginary vertical line with your eye — those names should line up with each other, and with the sleeve of the standing figure at the bottom of the design as well. The human eye craves structure, and wants badly for things to “line up.” We’d appreciate this poster more were that the case.

98. The Killers (1946)

98. The Killers (1946)

Again and again, Burt Lancaster is handled curiously on movie posters: it’s amazing how often he’s rendered in profile, holding a woman in his arms. The posters for Criss-Cross, Kiss the Blood Off My Hands, From Here to Eternity, and The Rainmaker all depict him this way. This one is the best of the bunch. He’s in love—she couldn’t care less. And even though the quality of the illustration is poor (that doesn’t really look like Ava, does it?), the overall composition more than makes up for it.

See how the long shadows cast by the killers lead us right to the doomed lovers? That’s an example of a designer using composition to keep our eyes from straying off the poster while also reinforcing the concept of the movie. I’m also conscious of the attention to detail: despite the small scale and extreme angle, anyone who knows this film knows that the killers on the poster are the very same killers from the film.

Finally, all designers will confide that the worst word to include in a design (especially a logo) is “the,” because although it’s insignificant as hell it almost always comes first! As you examine film posters, try to decide whether or not “the” is handled well. The designer here solved the pesky problem of beautifully; the designer on The Blue Dahlia poster, for example, did not.

97. Wicked Woman (1954)

97. Wicked Woman (1954)

Like the forthcoming poster for The Beat Generation, I’ve included the poster for Wicked Woman because it’s so unusual. It isn’t an attractive poster, but it can’t be dismissed, And there’s a bit more going on here than initially meets the eye.

It’s impossible not to catch the reference to Nathaniel Hawthorne: instead of a large “A” (and befitting the radioactivity of the atomic age) we are confronted with a woman who is quite literally glowing scarlet. In addition to the inventive (and economical) use of two ink colors, I love how the designer has made us into voyeurs. All of the poster’s scenes are domestic — amorous, violent, indifferent — and we peer at them as if through the panes of an uncurtained window. There’s something very much in keeping with the film noir milieu here; the poster reminds us that for many folks the American Dream was a sham, and not every 1950s home was a happy one. I’m annoyed by the lowest image panel — it seems unrelated to the two above; and for that matter the “vampire” panel is confusing as well. Although this poster asks more questions than it answers, it’s evocative enough to warrant a spot in the countdown.

96. The Beat Generation (1959)

96. The Beat Generation (1959)

Enter the realm of ugly but effective. As I mentioned at the beginning of the post, originality will be rewarded. Why? Because originality sticks in the memory — and being memorable is everything. I don’t mean to imply that designers and illustrators are vain; it just makes sense that a unique design will linger in the mind longer than something run-of-the-mill. It’ll also pull in more sets of eyes and sell more tickets. Besides, anyone who’s seen The Beat Generation knows that a traditional approach to the poster would have done the movie a disservice.

In one sense the design here is a mess: too many typefaces, type scattered everywhere, not a smidge of negative space to be found, and three or four clashing illustration styles. Yet what does this crazy mishmash tell us? That we’re in for a hypodermic’s worth of sex, violence, music, and weirdness — a “beatnik” exposé featuring a hot Mamie Van Doren. For the squares in 1959 middle America, something this lurid couldn’t be missed.

95. Highway 301 (1950)

95. Highway 301 (1950)

Here’s the first example I’ve included that exploits the semi-documentary style of many noir films. It almost reads like a newspaper page or magazine cover (we’ll see that approach taken to extremes later in the countdown) with “ripped from the headlines” style type-treatments all over the place, a radio-style “Flash!” at the bottom of the poster, and authentic-looking, scandal sheet crime photos along the right edge.

All of this visual noise frames a photograph of Steve Cochran pistol-whipping some cluck in a pinstripe suit. The expansive field of red in the background is also potently useful; it frames the artwork and anchors the many compositional elements, while suggesting a film that’s brimming over with blood and action. (It’s true—Highway 301 is brutal.) Through the choice of color, the immediacy of the shadows that morph into brushstrokes at the very top, and the diagonal composition, this vaguely recalls the Uncle Harry poster, but this arrangement wins out. All of the elements work together to complete the overall rectangular shape, and the Highway 301 title graphic points us leads the eyes to the poster’s unmistakable focal point: Steve Cochran—and it’s all accomplished with just two ink colors!

My one gripe? Five different typefaces is three too many!

94. Alias Nick Beal (1949)

94. Alias Nick Beal (1949)

Here we have a strong counterpoint to the poster for The Blue Dahlia. What that one did wrong, Alias Nick Beal does right. A simple, strong composition from top to bottom, it offers us a wonderfully colorful glimpse at Audrey Totter (even if the angle of her figure makes her hips seem strangely narrow), as well as a space-filling sketch at the bottom that provides some insight into the setting and the intrigue of the film. The characters have been arranged to accommodate the expansive red box that holds the film title and the stars’ names — and here we don’t have stars of such magnitude that they require the top of the poster to be wrecked, despite the fact that unlike the Dahlia stars, Milland was an Oscar winner. Finally, notice how the images of the performers are engaged with one another. Sure, Totter is objectified, but at least she’s attracted the attention of Milland, who in turn is eyeballed by Mitchell.

This is a rare film, so I won’t give anything away, but know that the three leads are depicted very much according to character.

93. Johnny Stool Pigeon (1949)

93. Johnny Stool Pigeon (1949)

I’d like this poster more if not for two things: first, the contrived publicity still pose of Dan Duryea (I can just see the photographer giving him direction, “Dan, hold the gun a little higher…”), and the fact that the designer has made it appear as if he is standing in Oscar the Grouch’s garbage can. The suggestion of violence is tantalizing, but why does the artwork have to be so forced and awkward? There’s also something amiss about the size relationship between Duryea and Mr. Lupino, whoops, I mean Howard Duff—in all likelihood they were not photographed together.

So why is it here? The saving grace of the whole affair is Shelly Winters, who looks extraordinary: iconic and noir-ish to the nines in her beret, red dress, and fox fur. This is exactly what a noir dame is supposed to look like. I’ve taken a fair amount of heat in the years since I originally published this countdown for not including the poster for that most iconic of noir films, Out of the Past. Although I made that decision in part to court some controversy, I’ve never liked OotP’s rather dull depiction of Jane Greer, whose image could have very well been lifted from the poster for an 18th or 19th century period piece.

92. Blonde Ice (1948)

92. Blonde Ice (1948)

The poster for Blonde Ice, one of the most legendary B-noirs, is another that benefits from not having to include big star names above the title. The use of photography rather than illustration (a low rent outfit like Film Classics wouldn’t pay an illustrator when stills or publicity shots would do) benefits this design. The gigantic image of Miss Brooks and her smoking gun, far from glamorous or idealized, suggests an intoxicating trashiness that’s what this movie is all about.

Looking past that, the design holds up under any microscope: dynamic composition, deft blending of type and image, and follow that wafting gun smoke that leads up to the lover’s embrace. If only Brooks’s line of sight conformed to that of the typography, and the boxy, smoke-obscuring drop shadow on the capital “I” could be removed—not to mention the clumsy and unnecessary shadow of the two lovers—this poster might finish higher on the list.

91. I Was a Communist for the F.B.I. (1951)

91. I Was a Communist for the F.B.I. (1951)

Nothing shouts B-movie like a two-color poster from the brothers Warner, and like the design for Highway 301, this is one of their best. Just as we appreciate films made on the cheap, I admire the economy of a poster done to match. If you haven’t seen it yet, this is a worthwhile film, strangely nominated for Oscar in the Best Documentary Feature category. It has also become widely available since I originally wrote about it years ago.

There’s really a lot to like in this design: check out how star Frank Lovejoy challenges the viewer, with even more immediacy than George Sanders in the Uncle Harry poster, breaking the fourth wall via that delightful quote. His arm points directly at the cascading vignettes of violence and sex, all guaranteed to entice audiences. Notice as well the wonderful title typography: not only does it use perspective to steer our eyes to the place Lovejoy’s finger points, but also it creates a “floor” upon which that lonely figure stands. Any designer capable of juxtaposing type and image this beautifully, while still maintaining the type’s readability, is aces in my book. Let it not go unsaid as well that audiences were sure to notice the prominent positioning of Warner Bros. and the Saturday Evening Post in the poster design: like putting the Good Housekeeping seal on your 1950s Red Scare exposé picture.

90. Short Cut to Hell (1957)

90. Short Cut to Hell (1957)

Primarily notable as the only film directed by Jimmy Cagney, Short Cut to Hell is a tepid remake of the Alan Ladd Veronica Lake classic This Gun for Hire. Regardless of the quality of the movie, this is one hell of a poster, and yet another that benefits from not having to promote a big name cast. Let’s take a few minutes and really sink our teeth into the design of this poster, because it’s that good:

The first thing to note is the poster’s simplicity, which allowed it to be produced on the cheap. There are just three colors, none of which are registered tightly, meaning fewer throw-aways on the printing press and significant savings over the course of the print run. There’s also little illustration, with images captured directly from publicity photographs. The top image has been manipulated—notice the inky quality of the trench coat. I bet that the publicity still was somehow different than what we see here. More evidence of retouching can be found in the strange cropping of the female figure’s front shoulder underneath the word “Short.” Designers were often given a sheaf of publicity shots and told to make them into a poster—they had to make do with what they were given.

What’s even better about the photos is how they create depth — this poster is practically 3-D. The hood being gunned down erupts from the picture-plane, falling into our laps! But his body also overlaps the title typography, which itself beautifully frames him. That type, in turn, overlaps the large image in the background. Each aspect of the image: the falling figure, the title typography, and the large photograph of the couple integrate seamlessly. Gestalt!

Now here’s the icing on the cake: take another look at the falling hoodlum. Where does his gun lead our eyes? Directly at the title of the movie. Where does his free hand point? At the cast list. Such positioning is certainly no accident! Now let’s look more closely at the big image on top. Where does that rather big, phallic gun point? You got it, and that’s no accident either.

Finally there’s the color, which is the mortar that holds these bricks together. The black ink really pops against the yellow and the red, but that large red rectangle is an incredibly powerful composition device, even more than on the Highway 301 poster. It gives the title typography, as well as the secondary typography, something comfortable to anchor itself to and align with; and it frames up all of the important information in the design. Like a picture frame, it shouts, “Look at me!,” and does it damn well.

Although there’s still a long way to go in the countdown, we aren’t likely to find many entries with better designs—there will certainly be more beautiful posters, more original posters, and more resonant posters, but few that are, as designers say, more designerly. Posters like this one make me love my job. What do you think?

89. Hoodlum Empire (1952)

89. Hoodlum Empire (1952)

What a great title! In addition to a stampede of westerns, lowly Republic Pictures issued several much beloved B crime films, with posters rendered in the studio’s house style: a cluttered hodgepodge of hand-drawn title typography, badly mismatched mechanical typefaces, and watercolor illustrations created from publicity stills. It would be easy to pass off Republic’s posters as the work of amateurs, but there’s something magical about how everything comes together in the finished product. I adore them—and poster collectors do too!

This design screams “B movie,” with an illustrative style that resembles that of a comic book. The images are cobbled together, the typography is clumsy, and the thing is convoluted as hell, but it all adds up to something really great. This may be another example of personal preference pushing objectivity aside for a moment, but this is one of those posters that evokes film noir in a way that, although I feel it in my bones, I have a hard time putting into words. No tip-toeing around Claire Trevor though, making yet another appearance in the countdown—and unlike the idealized version of herself appearing on the forthcoming poster for Murder, My Sweet, she is pure femme fatale here—that dismissive sneer says it all. Her illustration is so strong that it distracted everyone, even the artist (!), from the fact that the man holding her has two right hands!

88. Human Desire (1954)

88. Human Desire (1954)

87. The Big Heat (1953)

What is Glenn Ford’s problem? If I were Gloria Grahame I’d yank the cotton out of my mouth and tell him to get his mitts off me. My decision to place the posters for Human Desire and The Big Heat next to one another in the countdown was completely accidental—but let’s call it a happy accident.

Although both posters are winners, I prefer the immediacy of the startling image on The Big Heat to the superior composition of Human Desire, though Gloria Grahame is never sexier than on the Desire poster. Thus the ranking order. Another minor but important aspect of the Desire poster is that designers are “finally” coming to understand that placing quotation marks around the film title is silly and unnecessary.

We’ll have to forgive the era for the abundance of male on female violence that we see in film noir posters (there’s more to come, in terms of number of entries and the amount of violence). Interestingly, the moment depicted on The Big Heat poster between Ford and Grahame never actually happens: it’s Lee Marvin who grabs her like that in the movie! Perhaps the most interesting (and strangest) aspect of either poster is the odd appearance that a tiny Marvin makes in the margin of the poster for The Big Heat. What is he doing there? Who is he shooting at? Between Marvin on the Heat poster and the gigantic red shoe on Desire, I’m not sure which poster has the stranger details.

86. City of Fear (1959)

86. City of Fear (1959)

If we look at the posters from the silent era through the 1930s and 1940s, the majority were produced in the tradition of stone lithography popularized during the Art Noveau period: traditional illustrations wedded to hand-drawn typography in organic, curvilinear compositions. The design elements are nestled together like puzzle pieces rather than adhering to an underlying structure of imaginary horizontal and vertical grid lines.

Coming at the very last gasp of the classic noir period, the poster for 1959’s City of Fear demonstrates the evolving design style that was finally finding its way into the art of the film poster. This is most apparent in the unadorned, minimal composition, the selection of modern, photographically produced typefaces, and the designer’s reliance on concept rather than an idealized star image to sell the movie. The fifties were the beginnings of the information age, as well as the corporate era, and American graphic design took on a minimal, mass-produced look and feel—an outgrowth of the Swiss Modern style that flourished in Europe in the years after the war. This sheet for City of Fear is one that owes more to advertising sensibilities than it does to Hollywood poster-making tradition.

Yet it’s still something of a hybrid. The bedroom scene at the bottom of the composition and the trio of figures at the top seem old fashioned and out-of-style. The designer didn’t have the confidence (or more likely, the permission) to use only the frightened eyes and cityscape imagery, and must’ve felt compelled to include melodramatic moments from the film—no matter that they don’t seem to fit. The two figures at the top are bizarre: they nestle nicely among the red letters, but also appear to be clumsily falling through space.

85. Crime of Passion (1957)

85. Crime of Passion (1957)

A clearly communicative, cleanly designed, and professionally executed poster. Its late cycle date (1957) again demonstrates the slow but certain arrival of modernist design principles in film poster design: expansive areas of bright primary colors, crisp lines, typefaces instead of hand-lettering, and photography instead of illustration.

We’ve seen a few examples in the countdown so far where the poster begins to relate its own narrative by using the sequential panels of a comic strip. Crime of Passion comes the closest to resembling an actual comic strip. In this instance the technique is successful because it uses narrative in the same fashion as a movie trailer does: to whet the appetite. When we arrive at the end of the sequence—THE SIN, THE LIE, THE CRIME OF PASSION—we still very much want to visit the movie theater to learn how the story washes out.

Another nuance of the design that I appreciate is how the first two images are in the sequence are straightforward, almost unmistakable in their meaning, yet the third image is rather vague: has she just shot him? Is she about to? Has she simply just discovered the revolver among his things? We have to see film to find out, and that’s what makes this poster work.

84. Baby Face Nelson (1957)

I give you Mickey Rooney, snarling maniac.

There are a few posters that made the list through sheer bad-assery, and this is one of them. As you can see, Mickey adopted this rough-and-ready screen persona in two posters, though the design for 1959’s The Last Mile isn’t nearly as sophisticated as Baby Face Nelson’s; the type treatment at the top of the poster is forced and awkward, and the large, jowly face on the right is distracting. (I have to admit that I like the poster so much that I had to include it here as a bonus—the illustration of Mickey is too good to pass up!)

The clinchers for the red poster however are the ancillary images: how about the sprawling dead figures at the bottom? As you can see, all four have been bound and executed, their blood splatters and stains the floor all around them. This sort of imagery was risqué in any Eisenhower-era film, it’s shocking and notable to see it on the poster. And get an eyeful of shotgun-toting Carolyn Jones, of Morticia Addams fame. Too bad the poster artist gave her the gravitas of a linebacker in drag!

83. Appointment with Danger (1950)

83. Appointment with Danger (1950)

I’ve been an Alan Ladd fan for as long as I’ve enjoyed classic films, and back in the glory days of Netflix, when users could have avatars and publish reviews under their own screen names, Ladd’s face represented yours truly. Appointment with Danger is an excellent hardboiled film that has recently become available on DVD; it’s one I’ve written about here and at the Noir of the Week site. The poster for Appointment is super: eye popping primary colors highlighting two classic images of Ladd in action. As with the poster for Short Cut to Hell, I appreciate how the designer has used overlapping forms to give the poster a fore-, middle-, and background.

Ladd was a huge star at the time, so his name, along with that of Phyllis Calvert (who plays a nun in the film and is consequently absent from the poster) is above the title. Nevertheless, the type all sits comfortably, and the poster’s only real drawback is the black box at the bottom. It irks me how it covers up the tumbling figure of Jack Webb.

Referring back to the points I raised with the City of Fear poster, this poster is also one that bridges a style gap: none of the lettering here is drawn, it’s all the result of existing typefaces, yet the composition, with its large image of Ladd and ancillary action vignettes is pure Hollywood tradition.

One final distraction, which admitted kept me from moving this poster up in the rankings, is a little nit-picky: click to zoom in on this one and dig Jan Sterling’s right arm. Poor woman.

82. Lightning Strikes Twice (1951)

82. Lightning Strikes Twice (1951)

With taglines such as “A girl without a stoplight in her life” and “The first time you kissed her was one time too many,” all referring to the spectacular Ruth Roman (the look…the cigarette…priceless), how can a poster this delicious go wrong?

A great two-color design in the classic fifties Warner Bros. B-movie style (remember I Was a Communist for the F.B.I. and Highway 301?), this poster just doesn’t miss. The Post-It note-style box at the top bothers me in that the hastily scribbled type seems out of touch with the rest of the design, but it’s a small gripe. This is a stunner.

81. This Side of the Law (1950)

Here’s our first one-color poster of the countdown (there will be others, including one that ranks very near the top). At first glance the design for This Side of the Law is chaotic, with images and tag lines seemingly slapped down at random. However upon closer examination, we find the work of a skilled designer who really knows how to organize pictorial space.

The first thing to notice here is how the generous white border functions, in much the same fashion as a mat and picture frame: the illustration is busy, and the use of just one ink color makes it that much more difficult pick out details in the image. The designer understood that by providing ample white space around the image area, the poster would appear less chaotic. I also noticed how the white box near Kent Smith’s face actually provides some much-needed relief in the image’s most heavily shaded area.

Next let’s look at the balance. there are a whopping three tag lines, each designed in a different way! That’s busy and dangerous! The two tag lines inside the image area are each wedded to a nearby photograph, which allows them to finction as captions. Notice how the third tagline, that begins with “Trapped!,” is perfectly in line with the cast list and fine print at the bottom of the poster, as well as the image area itself. Our eyes love it when things “line up,” and by sizing the type thus, the rectangle-within-a-rectangle effect is enhanced and the elements in the center of the poster become clearer.

Just to drive a few of these points home and understand how two posters can be similarly constructed, yet wildly different, I present the barking dog of a one-sheet for 1962’s big-budget Cape Fear. Was Mitchum ever done a greater injustice than he is on this poster? Furthermore, if we haven’t seen Cape Fear yet, wouldn’t we assume that Gregory Peck is the villain?

80. The Verdict (1946)

80. The Verdict (1946)

Here’s another of the great limited palette posters from Warner Bros. Yet unlike so many of the others done in this style, this example unusually uses just a single photograph to shoulder the weight of the entire poster. No insets, no taglines, no cheesecake, and no violence; just a deliciously dark photograph of the film’s three leads looking off-screen, riveted by some unknowable nemesis.

The title typography is great—this is one of the first instances of a conceptual type treatment we’ve seen thus far. It appears to have been stamped, in red ink of course, by some colossally large bureaucrat with absolutely terrific force, as if on a correspondingly large manila envelope. It hangs in the air, looming above the three unsuspecting characters that strain under the weight of the verdict itself. The oversized red box that holds the star names is the only major drawback — as if the photograph couldn’t do the job of identification just as easily—after all, Lorre and Greenstreet were stars of the first order. The box is too big; it covers up too much of the photo, and weighs the whole thing down. It also bothers me that the red boxes are perfectly parallel to one another; if the lower box were set at a different angle, we might also get the impression of the boxes tumbling through space, as surely the characters in The Verdict must be.

79. Stranger on the Third Floor (1940)

79. Stranger on the Third Floor (1940)

Stranger on the Third Floor is one of the few films credited with being the very first film noir, though enthusiasts can spend hours arguing about it. Although the poster is done in the classic early forties style, it nevertheless captures the paranoia and alienation that are the hallmarks of film noir. My major qualm is that the accusatory hand pointing at all of those nervous faces might suggest to some viewers that this is a simple whodunit murder mystery, a style of film that was very much en vogue as the 1930s become the 1940s. Nevertheless, the faces are so vividly expressionist and well rendered—especially Peter Lorre’s—there’s little to complain about. I wish the title typography didn’t so sloppily cover up some of the faces—if it didn’t this would have been ranked higher.

78. Side Street (1950)

78. Side Street (1950)

This was one of the more difficult entries to situate in the countdown; I’m still not confident about where it ended up. Just to be perfectly clear, I feel as if I might have placed Side Street too high, rather than too low. The illustration of Granger and O’Donnell is very reserved compared to that seen on many of the other entries—which is something I appreciate. There’s a quiet elegance happening that I wanted to reward, along with the use of the sign motif that we’ll see again on the poster for Detour—very iconic for film noir. Once again I’m pleased with a strong diagonal composition, divided in half by the sign pole. However, I find the photographic imagery at the poster’s left edge to be disappointing. It’s awkwardly presented, with halftones that are somehow lighter than the surrounding blue-purple background. Such gray shadows aren’t very seductive, and instead give the poster a cheap, unfinished look that almost wrecks it. I think we’d have a better design if those images could be removed, and the “fate dropped…” tag shifted into that area.

77. The Bonnie Parker Story (1958)

77. The Bonnie Parker Story (1958)

Sheesh, what’s not to like? In case you can’t see it very clearly: it’s a beautiful woman with a tommy gun and a cigar. Yes!

Seriously though, score one for a great illustration of cigar-chomping Big Dottie Provine. I love the broken glass effect—a terrific solution to a daunting illustration problem. It’s almost an optical illusion, appearing both in front of her and to the side. The type treatment at the top is boring (though clean), but the poster has one of the best taglines ever: “Cigar Smoking Hellcat of the Roaring Thirties.” You can’t beat it.

76. A Blueprint for Murder (1953)

76. A Blueprint for Murder (1953)

Do I really need to explain this one? Although I mentioned at the outset that how honestly and accurately the poster represents its film is important to me, the red-blooded American male in me takes it back. The poster design tells us little about Blueprint’s story; it gets by on simple cheesecake alone. Nevertheless, the design is still well assembled. Nice title type treatment in the red box, even considering the cliché of using the stencil typeface to make us think of blueprints—at least the box itself isn’t blue, right? The names are up top where we’d rather not see them, but they balance the two images to their left quite well, and despite the brazen yellow color they do nothing to distract us from Peters, doing her best to lure ticket buyers into the theater.

75. Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954)

75. Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954)

We get back to our low budget roots with this poster, which looks fantastic in three colors (black, red, and yellow; the paper is white).

How do you handle a film that boasts no star power? Simple: you overload the design with violence and action. I don’t envy the designer who had to sift through all of the production stills that eventually found a place in this composition, but I do wonder if they are all actually taken from this film. Dig the violence: everyone here is swinging a pipe or a club, Neville Brand is wielding some sort of prison yard shank, while a Barney Fife-ish screw is desperately trying to call in some help at the top right. An impressive, well-executed (ouch) photo-montage, especially considering it was done decades before the advent of that modern monstrosity: Photoshop.

74. The Mask of Diijon (1946)

Yet another poster that makes a strong noir statement, this time one of alienation. The sullen, paranoid expression on Erich von Stroheim’s face, in contrast with the serenity of the blonde, brings to mind the warped perspective of many noir protagonists. The dark colors further enhance the mood.

Another reason that this is such an interesting poster is that it begs viewers to ponder what’s actually going on. For the record, von Stroheim is actually a magician in the process of performing a trick, although it appears at first glance to be something altogether more grotesque: we think we are seeing a man with a woman’s decapitated head in a wicker basket. He almost appears to be seated on a train brooding over the passing landscape. This sense of ambiguity and melancholy is powerfully noir-ish, and makes for a titillating advertisement for the film. Bizarre but effective.

73. Detour (1945)

73. Detour (1945)

The only thing missing here is a vivid depiction of Ann Savage. Sure, that’s her leaning up against the light post, but she and Tom Neal look more like pals than anything else, and anyone who’s ever seen Detour will tell you that they are about as far from being pals as two people can get. Nevertheless, this scores gigantic points for the use of film noir iconography—the street sign and lamp post—and unlike the Side Street poster, the designer was able to turn the sign’s warning stripes into a frame that holds the entire composition together.

The interior imagery is nicely composed from illustrated movie stills, though I’ll nitpick the inexplicable white space left between the clarinet player’s arms. On the plus side, note how well the artist has utilized overlapping to integrate the frame and street sign with the artwork—it’s subtle but effective.

Finally, you just can’t go wrong with a street lamp, even if it is in color. An interesting, and modestly successful artistic attempt to translate the beams of light into stylized forms.

72. The Glass Key (1942)

72. The Glass Key (1942)

Is that Veronica Lake or Kathleen Turner?

What makes the world go ‘round here isn’t all of the imagery inside the key shape, it’s the key shape itself, combined with a vivid pallet and straightforward typography.

This is, perhaps, the most phallic poster in the countdown, but while I acknowledge the shape of the key (which is a marvelous organizing concept), it’s sexual connotation doesn’t make me appreciate the poster any more or less.

The problems here aren’t insignificant: the image of Lake doesn’t do her justice, and the rest of the vignettes are far too redundant: men clutching and punching at one another, all obviously posed. This is still a strong poster, but too bad the interior artwork wasn’t a bit more creative. After all, there’s a lot more going on in The Glass Key than fisticuffs. If we could go in and replace a few of those images this would skyrocket up the list, possibly into the top 20 or 25.

71. The Big Bluff (1955)

71. The Big Bluff (1955)

One of the cheapest, trashiest posters in the countdown—I absolutely love it! The no-brainer influence here is undoubtedly Confidential magazine: the colors, inset photographs, and of course, the ‘violators’ (Sorry, that’s design-speak. Those red rectangles with black type in them; I don’t know what else to call them!) in the upper-right corner of the design all intentionally evoke Confidential.

Directed by W. Lee Wilder (the great Billy Wilder’s brother, believe it or not), this is a true low-budget gem. The film itself is actually not as trashy as the poster suggests, but I still recommend this—it’s available as a bargain DVD. What a great central photo, with its vivid reds and blues. Just one question: what in the world is going on with the bongo player?!

70. The Garment Jungle (1957)

70. The Garment Jungle (1957)

In addition to a large slice of cheesecake, the poster for 1957’s The Garment Jungle more than holds its own in terms of artistic merit. Voyeurism is a recurring theme in film noir (as we’ll see in some higher-ranked entries), so the keyhole point of view image of the model, who’s either dressing or getting undressed is certainly in keeping with the noir milieu. However, it’s the scissors that make this poster so unique and memorable. The hand / scissors motif is potent in so many ways: it adds spatial depth; it “cuts” the picture plane diagonally, providing edges that typography aligns to; it creates a negative space that holds a tagline and small action-image; and finally, it integrates with the background and the nice little garment tag that holds the title of the film. Finally, and most importantly, it portends violence and death. Notice also how that negative “white” space mirrors the angle and shape of the model’s body—that’s no accident!

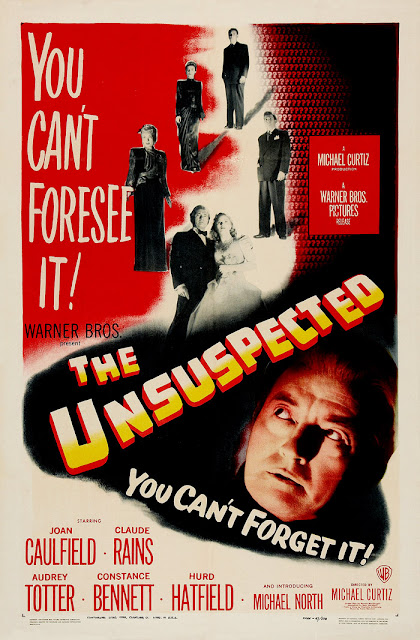

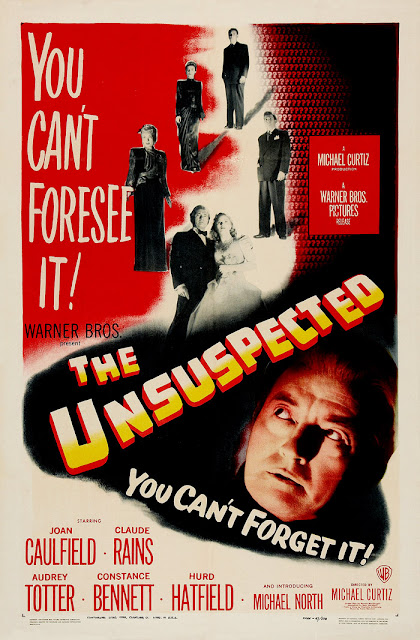

69. The Unsuspected (1947)

69. The Unsuspected (1947)

Black, white, and red are very potent colors—designers often go straight to them when they need to create something that pops. The colors work great here, with a little touch of yellow in the title typography contributing a nice visual surprise.

The composition is excellent: the positioning of the figures at the top is fascinating both pictorially and conceptually, and create in the poster a tremendous amount of visual depth. The juxtaposition of those figures and the title typography (remember we love diagonals!) with Claude Rains’ large face, staring directly at them, is quite striking. If this is marred by anything it’s too much type — I’d like nothing more than to simply wipe away the awkward “You Can’t Forsee It!” and “You Can’t Forget it!” lines, and leave the left-over spaces empty.

This is a poster that rewards those who appreciate the little details: notice the exquisite little pattern of question marks in the top right quadrant of the poster. Subtle and wonderful.

68. No Escape (1953)

68. No Escape (1953)

San Francisco is one of the preeminent film noir locations, yet few noir movie posters actually integrate the city into their design. No Escape, a B-thriller of zero reputation, is that rare poster that manages to capture the noir-ish mood of San Francisco, even if much of the city’s power is dulled amidst a sea of yellow ink.

Similar to the poster for The Big Bluff, the poster for No Escape is included primarily for the way in which it embodies the characteristics of noir, rather than for the merits of its design. And while the poster certainly has its share of flaws—even more than The Big Bluff—it’s important to recognize that the rough, unsophisticated, thrown-together quality of many B-movie posters actually enhances their impact. So while this design is cluttered, oddly split vertically into halves, and lacks a focal point, its use of the San Francisco skyline and the gun-toting silhouette more than make up for its formal shortcomings. Besides, you just can’t beat a poster with a cowering hoodlum with a bottle of liquor poking from his jacket pocket—what’s more noir than that?

67. Women’s Prison (1955)

67. Women’s Prison (1955)

Sure, it’s exploitation-noir, but c’mon, what a great poster! I’ve included it as another example of the “ripped from the headlines,” Confidential magazine design style, in addition to a pretty solid design aesthetic. It succeeds on the strength of its boxy, comic book style composition, and its surprisingly cohesive use of typography.

Cleo Moore isn’t well-known out side of film noir or Hugo Haas circles, but she always got the big star treatment from her poster artists. Ida Lupino was an A-lister and a household name at the time, Moore wasn’t—but it sure says something about Cleo’s appeal when she gets treated better than Ida on a film poster. Not to mention the other ladies in the film’s impressive roster of actresses, including vamps Audrey Totter and Jan Sterling. This film is arguably more camp than noir, but it’s a lot of fun no matter how you look at it.

On a side note: how about the subtle fifties materialism inherent in the taglines?

66. The Shanghai Gesture (1941)

66. The Shanghai Gesture (1941)

Here’s a truly classic Hollywood studio poster that gets in on sheer beauty. The Von Sternberg film was released in 1941 and stars an impossibly young and beautiful Gene Tierney. It’s really a proto-noir more than a fully-fledged film noir. I love how ‘drawn’ this feels, especially after so many posters from the fifties that rely on photography. In fact, the only drawback is the use of the three inset photos—if only they could be stripped away! Nonetheless, the illustration of Victor Mature and Tierney, framed by the sweeping dragon and title typography is incredibly evocative of the film’s promise of intrigue.

65. Ride the Pink Horse (1947)

65. Ride the Pink Horse (1947)

Long has Ride the Pink Horse held a place in my heart as the greatest film noir title of all time (along with Kiss the Blood Off My Hands), and I love the poster nearly as much. For my money this is the best image of Robert Montgomery on a film poster, and any image whatsoever of the divine Wanda Hendrix is welcome anytime. It’s a bizarre poster to say the least: a “Hotel Stack” collage illustration scheme, some highly incongruous and suspect typography, a bizarre cartoon-style scene at the bottom, and a shade of green that brings poison gas to mind. Yet for some reason (and probably a visceral one, at least as far as I’m concerned), it all works. The power of gestalt is happening here in some wonderful way and turns this into a poster that just grabs at you. Combine its super magical power with Montgomery’s intense gaze and the poster lands a spot here in the middle of the countdown. This is one of those times where being offbeat goes a long way to the positive.

64. Johnny Apollo (1940)

64. Johnny Apollo (1940)

Here’s a poster from Fox that set the standard for those black, white, and red posters from Warner Bros. There’s nothing about the design for 1940’s Johnny Apollo that really shouts at you, but there’s a lot to enjoy in the details. And I’ve placed it here in the countdown because it anticipates all of those of the fine Warner posters we’ve already seen. I love the palette: the warm sepia tones of the photography and the secondary type combined with black and the rich red of the title. The attention to detail in the text type is a plus as well, showing us that the designer really cared about the quality of the finished piece—a dedication to craftsmanship often absent from the mass-produced, mechanical style of the posters of the 1950s. The combination of script typography for the first names, with big bold surnames in deco-style hand lettering is just beautiful, as is the cheesecake photo of Dorothy Lamour. Edward Arnold’s part in this film is huge, so his presence in the poster is necessary, but I’d like this a bit more if we could nix him while “reflecting” the photograph of Tyrone and Dotty in order to get their faces to fall underneath their names.

63. Pickup on South Street (1953)

63. Pickup on South Street (1953)

This is one of the great noir pictures; if you haven’t seen it move it to the top of your list. If we can make the argument that Edward G. Robinson gives the greatest supporting turn of all time by a male actor in Double Indemnity, then an equally strong case for a supporting actress can be made for Thelma Ritter’s in this film. It’s Sam Fuller’s best movie, and maybe Richard Widmark’s as well. Tough, cynical, and subversive; this is everything a mature film noir ought to be. The poster is fine: nice title type holding up a traditional, if a bit too-symmetrical composition. The star names are down at the bottom where they belong, and the inset images give us an idea of the film’s content, while nicely framing up the large artwork of Peters and Widmark. The white background isn’t very indicative of the movie’s dark subject matter, but it sits well on the poster and contributes to the all-American color palette, which is ironic given the movie’s cynical jab at the government.

62. Cop Hater (1958)

62. Cop Hater (1958)

William Berke’s 1958 Cop Hater was one of the very first movies I ever wrote about here. It’s a late-cycle film noir, so the look and feel of the design (particularly in how the tagline is handled) greatly portends the design aesthetic of the movie posters of the 1960s.

The design uses vivid primary colors to create “pop” and attract the attention of ticket buyers, while placing the Amazonian Shirley Ballard front and center in the eyes of male viewers. The romantic imagery, along with the poster’s use of color and the design of the tagline almost make it easy to imagine this as a comedy in the spirit of Rock Hudson and Doris Day, but the sex and violence keep this firmly grounded in the noir arena. Meanwhile, the poster’s forward-looking design style makes it one of the more original entries in the countdown, especially when compared to the classic feel of The Shanghai Gesture, which appears just below it in the countdown.

61. Storm Warning (1951)

61. Storm Warning (1951)

The always underrated Ginger Rogers stars alongside Ronald Reagan and scene-stealing Steve Cochran in the KKK-noir Storm Warning. The two-color Warner Brothers house design style on display here should feel familiar by now—this is likely by the same by the same designer responsible for the posters for I Was a Communist for the FBI, Highway 301, and Lightning Strikes Twice, as well as a few entries yet to come.

I use the term “designer” rather than “artist” in this instance very deliberately! The designer’s training—the hard-won ability to perfectly marry concept, typography, illustration, photography, and pictorial space is evident here as it is in very few other entries. This poster isn’t effective because of the quality of a drawing or painting, or a vivid color pallet, but rather through the thoughtful and masterful arrangement of type, image, and space. This design is not likely to adorn many walls, but it most certainly attracted attention and sold tickets.

All of the qualities that made the designs mentioned above great are present here: a simple, dynamic composition; strong type choice and alignment; large white frame; boxed tag lines; and so on. Yet this design has more impact than those we’ve seen before: look closely at the terror in Ginger’s expression, notice how strongly it resonates with and reinforces the message of the tagline, and the incredibly clever cloud-like shape of the image area. Very strong: the title is at the top and the cast is at the bottom, as it should be; with the width of the cast names helping finish out the rectangular image area—it’s something of a signature style with this designer. Wish we could put a name to some of these folks!

60. The Wrong Man (1956)

60. The Wrong Man (1956)

Here’s a poster that breaks all the rues and gets away with it. There are no large images of the stars, the title typography is too small and too hard to find, and there’s too much text type! And yet, precisely because this poster is so unorthodox, it must have really attracted a ton of attention. We talked briefly about voyeurism in the entry for The Garment Jungle, and here it comes again. This idea of secret watching, or of being watched, is an important noir motif, and it’s out in force here. Consider all of the ways in which the image of a put-upon Henry Fonda could have been depicted, yet the designer chose to give us this view, of Fonda being watched surreptitiously by some unknown assailant. The poster conceptually suggests that we too are about to take on the role of voyeur; and it isn’t lost on me that the round field of the car mirror is also oddly reminiscent of a microscope or detective’s magnifying glass. Some aspects of the design are forced: the angle of the car is strange, as is the placement of the mirror on the windshield, but both are necessary in order to get the mirror into the proper place in the composition, and at the best size.

59. Scandal Sheet (1952)

59. Scandal Sheet (1952)

From top to bottom, this is a well-executed poster in nearly all regards. Thank goodness Brod Crawford wasn’t a matinee idol, otherwise we’d have a completely different poster, most likely with a large image of him and a woman in some sort of embrace. Instead, we get a noir-ish full figure with the big fella in a coat and hat, gun in hand—strikingly lit, even in the illustration. He stands upon (no, it isn’t a pillow) one of the many crumpled newspapers that blow through the canyons of Manhattan. In the film Crawford plays the editor of such a newspaper—one who uses heartbreak to drive circulation, until he gets a dose of his own medicine. The integration of the Crawford with the big sheet of newsprint serves a dual purpose: it’s obviously conceptual, but the newspaper also gives the artist a nice field upon which to place the title typography. Here’s a really subtle detail, I wonder if you noticed it? Check out the final letter in the title—see how the crossbar on the “T” in “Sheet” just gets cut off? That’s attention to detail.

The tagline at the top is well done, especially in the juxtaposition with Crawford. The same can be said of the Confidential-style inset photographs. For the umpteenth time it is made evident how the use of diagonals can invigorate a design. Two small qualms: First, I’m having a hard time figuring out the blue area at the bottom of the poster. My best guess is that it is meant to be a spotlight of sorts, the same that illuminates Crawford. If that’s the case the shadows don’t quite work and the leftover red, white, and blue effect seems a little out of place. Finally, the color transition above Donna Reed’s head is sloppy and awkward.

58. Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950)

58. Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950)

Feel free to argue with me on this one, it’s another poster that I struggled to place in the right spot in the countdown. Along with the forthcoming poster for The Verdict, this one features title typography that functions conceptually, in order to drive the message of the film home to viewers.

Let’s ignore the sub-par illustrations of Dana Andrews and that generic broad somehow meant to be Gene Tierney; all the good stuff here is happening in the box with the title typography. On the whole, this poster should be darker, and much of what the artist has made blue should be black, but there is something powerfully noir-ish in the use of yellow here. We’ve seen yellow used so often before simply for its brightness and ability to contrast with black. Here, we have the yellow of a streetlight harshly illuminating the drama playing out amongst the typography. Whatever is happening under the harsh glare of the lights is fascinating—why is that man dragging a body?—and viewers are certain to have wanted to see more. Finally, the conceit of the type “ending” along with the sidewalk itself is conceptual and witty and provides the designer in me a chance to spend a few minutes simply enjoying the skill with which the artist was able to wrap the type along the curb while maintaining readability. Any professional designer will tell you that effects such as this, no matter how simple and effortless they appear to be, are notoriously difficult to get right.

57. Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956)

57. Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956)

What would a noir poster countdown be without that particular facial expression from Joan Fontaine? I guess it’s a little ironic that I should accuse Joan of having limited facial expressions when she’s depicted alongside an actor as wooden as Dana Andrews. Make no mistake, I love the guy dearly—if you read my essay on The Fearmakers you’ll know how much. Nevertheless, Andrews’ range wasn’t one of his strong suits. The poster here is quite nice, with the puzzle pieces doing exactly the same thing as the question mark in the forthcoming poster for House of Numbers and the title typography in the poster for The Verdict—it looms over the main characters, casting an ominous pall over their lives and their fates. It’s the burden they must suffer under. Here the pieces seem to be closing in on the couple, like some angry mob, shortly to overwhelm them—or at least, one of them…

56. Brute Force (1947)

56. Brute Force (1947)

It’s almost every film noir fan’s favorite prison picture, and the movie is hard-boiled enough to live up to its title. I have to admit that it’s also nice to see Burt Lancaster looking tough for once, and not wrapped in the arms of his latest paramour. A superb poster that gets the job done without the use of photography, this features vivid, stylistically consistent illustrations from top to bottom in the form of an “L” shape that frames the equally gritty title typography.

Note how tactfully the cast listing is handled in this example: the designer had to include the names of eleven different performers, and place them in some sort of hierarchy according to gender and billing. It works really well, and the accompanying prison-style taglines are a nice touch. This is a busy design, but if we first encounter this poster from a distance we’ll notice the big image of Burt and the title—the only things necessary to get us to approach, learn more about the movie, and ultimately enter the theater.

55. House of Numbers (1957)

55. House of Numbers (1957)

Jack Palance, he of the chiseled face and the one-armed pushup, makes two appearances in this part of the countdown. The poster for House of Numbers may initially slip your notice—it did mine. Yet with each viewing it resonated with me more and more—so much so that I finally tracked down a copy for my collection.

The poster features an iconic representation of Palance, one of film history’s greatest faces. And yet it’s the gigantic question mark that makes this poster tick, how it represents the monkey on Jack’s back, and the way in which the small images inside the question mark invite the viewer to solve the film’s mystery. After all, House of Numbers is a prison-break picture—and a pretty good one, even if a little far fetched.

Readers are liable to think I’m screwy on this last point, but I love these little instances of visual surprise and non-conformity: check out how the red shaded area leeches down into the white frame of the poster for absolutely no good reason. Why does it do that?! Jack’s body stops at the edge of the frame to allow for the fine print, why not the red? Who knows, maybe it’s a mistake—but an intriguing one.

54. I Died a Thousand Times (1955)

54. I Died a Thousand Times (1955)

Most of you already know that this is a remake of 1941’s High Sierra, with Jack Palance and Shelley Winters in the Humphrey Bogart and Ida Lupino roles from the earlier film. Palance lacked Bogie’s pathos, and Winters was missing Lupino’s vulnerability, so the remake falls short of the original, but the poster is still a gem.

It’s also worth noting (and this might help explain some of the design choices here), that unlike High Sierra, I Died a Thousand Times was shot in color. The poster is simply marvelous. I don’t feel compelled to explain this one away, I’m sure you are all on the same page with me. It’s just a stunning design with a wonderfully stilted composition and vivid use of color. The large image is sexy as hell, and all of the panels combine to form a fantastic broken stained glass effect. And can you beat a film with Pedro Gonzalez Gonzalez in the cast? Somebody get me one of these!

53. Black Tuesday (1954)

53. Black Tuesday (1954)

My affection for the great Edward G. Robinson is practically limitless: I wrote a film noir biography of EGR for the Film Noir Foundation, and Black Tuesday is my favorite Robinson film. It came at the time that the great man was forced to make a stream of B crime pictures because of his run in with the red baiters and subsequent gray-listing. It’s widely known that Robinson found this work on the poor end of the business distasteful, but it’s hard to blame him: his life was so miserable at the time that it’s difficult to imagine him having positive feelings about anything. Not only was his marriage a failure, his wife was mentally ill; his son gave him nothing but trouble; and he couldn’t grasp how the country he adored and to which he was devoted could treat him so poorly, and even call him a traitor.

All of Robinson’s feelings bubble to the surface in Black Tuesday—his performance is terrifying. It’s a rare film, but one very much worth seeking out. The poster is darn good as well—it’s one of the few times that Eddie gets the full-figure treatment in one of his posters. Owing to his unconventional looks and build, he often appears as a head floating in the background in order to make room for the romantic leads. Check out an earlier Robinson poster, Night Has a Thousand Eyes, as a prime example. At any rate, it’s a great shot of a gun-toting Robinson, and the crosshatched / wood engraved illustration technique is fairly rare for a film poster. Yellow is a color we see more than any other, often unfortunately, but here it’s a hit. The color palette here, black and the primaries, really makes this pop out, as does the quality negative space that forces you to confront the image of Robinson. There a lot of typography here, possibly too much because the title gets lost, but it is well-stacked and the little square of negative yellow space balances the larger space above Eddie very cleverly. My favorite part: dig that little electric chair. Zap!

52. Blonde Alibi (1946)

52. Blonde Alibi (1946)

Look at those gams, that plunging neckline, those “Victory Roll” curls. Holy smokes, sometimes design has to take a back seat to a blonde in a red dress—but this isn’t that time, because the design here is as delightful as the girl—or is it just as “bad” as the girl? Sometimes noir gets confusing. Seriously though, what a great noir statement this poster makes: the idealized and idolized woman surrounded by all the chumps and suckers who revolve around like so many satellites. Great colors, super composition, strong type treatments (especially in having Martha seated on the box that contains the cast names—talk about getting your money’s worth out of a simple box), quality negative space, and I’ll say it once again: the girl in the red dress. We’ll see better cheesecake posters before we get to the end of the countdown, but not by much.

51. Too Late for Tears (1949)

51. Too Late for Tears (1949)

Of course it’s possible that some readers could be bothered by the inclusion of a poster such as this in the countdown (though we’ve already seen a few milder examples in the posters for Wicked Woman and The Big Heat), but such violence and imagery are inescapable aspects of the film noir underworld, and I make no apologies for including such posters. My one qualm is with the illustration of Scott, who looks more like Cybill Shepherd than she does herself. Otherwise this poster is a home run: the extreme scale of the illustrations of Duryea and Scott, the competing diagonals running all over the place, and the critical placement of the tagline. Dig how the tagline appears to be coming from Duryea’s mouth, practically comic book style. This puts the violence into an almost cartoonish context and makes it that much more palatable. My favorite thing about the illo is also the most subtle, and that’s the slick foreshortening of Scott’s left arm. Speaking of comic books, it’s almost Kirby-esque in how it creates depth and movement, and ties together the illustration with the yellow box and the narrative scene in blue at the bottom of the composition.

For those of you who may not have seen this yet, that scene depicted at the bottom is crucial, and sets up all of the drama of the film. If you do track this down though, make sure to score the high-quality restored print from the Film Noir Foundations. Too Late for Tears has been in the public domain for a long time, and there are hardly any unrestored prints out there that are actually worth watching.

50. Murder, My Sweet (1944)

50. Murder, My Sweet (1944)

This poster, aside from its obvious beauty, is one crafty piece of movie marketing. Let’s think about another film for a moment, one I’ve written about here on the blog in one of my most visited posts: Christmas Holiday with Deanna Durbin and Gene Kelly. Imagine yourself in the winter of 1944, suffering under the brunt of gas rations, food rations, maybe even worrying about a loved one somewhere. You decide to take a break from life’s troubles for an evening at the movies—they’ve got the new Deanna picture over at the Strand, and this one co-stars that new boy, Gene Kelly. You see “Christmas Holiday” on the marquee, and in you go—for what turns out to be one heckuva dark, paranoid melodrama, not the light and whimsical holiday picture you thought you were going to see.

Much the same can be said of Murder, My Sweet, the movie in which crooner Dick Powell reinvents himself as wry and tough private detective Philip Marlowe. Although the title of Raymond Chandler’s source novel, Farewell, My Lovely, was changed so as not to really put the whammy on potential ticket-buyers, the poster straddles the fence between Powell’s old and new screen personae brilliantly. Take a look at the rather stunning, yet purposefully ambiguous illustration of Powell and Trevor and ask yourself if you are looking at an advertisement for a crime story or a musical—with this poster, who knows? By not having the pair in a tighter embrace, or actually kissing, it was very easy for viewers to imagine that Powell was serenading his girl; after all, that’s what they expected from him at the time.

For such cleverly manipulative thinking coupled with a positively exquisite illustration, Murder, My Sweet lands here.

49. Chicago Confidential (1957)

49. Chicago Confidential (1957)

You guys all know why this one is here, so instead of lauding it as an example of great design work, instead it gives us an idea of the extraordinary power and popularity of Confidential magazine. For those of you who aren’t familiar with Confidential, it’s the original scandal sheet, and was one of the most important pieces of fifties pop / Hollywood culture. Recently the subject of a book I haven’t had the chance to read yet, Confidential and its bizarre history are worth looking into.

48. The Threat (1949)

48. The Threat (1949)

Felix Feist’s The Threat is one of those noir films that few other than hardcore enthusiasts have seen, and they carry a torch for it. The poster moves, with various elements surging from one area of the composition to the next. The designer gets a ton of mileage out of that large, sweeping red brushstroke, which encloses the title and leads the viewer’s eye to the illustration of crime pic icon Charles McGraw.

The next point is subtle, almost certainly the unconscious product of the artist’s intuition, but note how the heads of the three figures above the title mirror the swoosh of the red brush stroke—both in the similarity of the curve of the arch, and in how that movement surges outward from the face and body of the gun-toting McGraw at the top of the poster, down through Virginia Grey, and finally to Michael O’Shea’s face. Perhaps there’s something a bit campy about the three heads on the left and their accompanying tag lines, “Must HE die?” and so forth, though what some might find corny, I think, at least in this instance, is pretty cool.

47. Night has a Thousand Eyes (1948)

47. Night has a Thousand Eyes (1948)

Fantastic poster, so-so movie. Despite the fact that this film was made when Edward G. Robinson was on the outs with the Hollywood establishment, suspected as a communist sympathizer, his star power was such that he still got his name printed, quite literally, above the title. The three names up top are something of an eyesore, making the design feel crammed into the bottom two-thirds of the space, but nevertheless this is a wonderful poster in the classic Hollywood style. It’s ironic that the title typography is situated amidst a sea of stars—at the bottom of the poster! Certainly this one would appear much higher on the list if that text could move to the top of the design while the stars’ names sank to the bottom. So it goes.

Poor Eddie, he never seems to get his entire body into a poster design—instead his face is always floating in the ether, larger than life. Still, this has a strong triangular composition; it depicts its three leads well (though William Demarest walks away with this movie); and the Dali-esque title typography is out of this world and has made this poster extremely expensive. While I really like the small action illustration of the woman jumping in front of the rushing locomotive (yikes, what a spoiler!), it’s the wonderful title type that makes this one rate so high.

46. I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes (1948)

The noir themes of angst, persecution, and alienation that are so prominent throughout Cornell Woolrich’s novels are incorporated beautifully in this compelling design, and consequently the poster for I Wouldn’t Be In Your Shoes finds a higher place in the countdown than it would merit on visuals alone. I loved writing about this movie.

I’d like this design so much more if we could diminish the dishonest depiction of Elyse Knox (she’s not a femme fatale in the film, though she’s presented as one here), and make the trio of pointing fingers much more powerful. Perhaps we could also shift the gun-pointing Regis Toomey to the opposite side and pose him so Don Castle’s big mug was squarely in his sights.

Finally, try to imagine the aqua-greenish color at the top as a deep blue (or even black)—better, right? Don’t get me wrong, I’m not trashing the design here, I’d be happy to hang this poster on my wall. The use of faces rather than full-figures or busts give the poster a lot of punch—Castle’s head has to be at least a foot tall!

45. The Stranger (1946)

45. The Stranger (1946)

I’m including this poster almost entirely on the basis its exquisite illustration. The typography is generally sufficient, though it’s far from exciting and is gives the poster an awfully unbalanced and unstable foundation. (The blue block of color in the lower left corner is simply awful.) But the illustration is pure magic, and the color palette is absolutely marvelous. Loretta Young’s performance in The Stranger is a bit hysterical for my tastes, but she’s ravishing on the poster. Note how her face is the poster’s sole source of light, illuminating both of her costars. Aside from the sophisticated technique, it’s nice to see such a well-executed portrait of Edward G. Robinson, not to mention Orson Welles, though both pale (quite literally) next to Young. What really gets this going though, and keeps the triple-portrait from becoming stodgy are the vibrant colors and the subtle magic of the background—the brushstroke style activates the background and give the whole poster a sense of movement. Like the next poster in line, for The Postman Always Rings Twice, this isn’t perfect, though parts of it are.

44. Raw Deal (1948)

44. Raw Deal (1948)

A Poverty Row product made by rising stars director Anthony Mann and cinematographer John Alton, Raw Deal is one of the more revered film noirs. As for its placement, for the first time in the countdown (and hopefully the last) I think I got it wrong. Looking at the poster again to write the blurb, I’ve realized that it just doesn’t stack up to the quality of the entries around it, and I’d shuffle it backwards ten or fifteen spaces if I could. What originally pushed it up this high was the powerful image of Dennis O’Keefe spotlighted against the brick wall. It’s an illustration that longtime film noir enthusiasts encounter often—clipped from the poster and used as a prop on all sorts of noir websites and publications. That aside, I think the cobbled together elements that make up the rest of the poster just don’t hold water.

I appreciate the title typography but it reminds me too much of the sort of lettering you’d encounter in a prison picture from the previous decade, and the two words are simply too far apart. The arrangement of the other elements in the design is too loose, even though effort has been made to constantly steer the viewer’s gaze toward O’Keefe. The black type boxes at the tp and bottom of the design are wholly unnecessary, and I have a sneaky suspicion that the image of Claire Trevor has been borrowed from another film.

43. Police Reporter (1947)

43. Police Reporter (1947)

Many of you will know this Poverty Row entry by its other title, Shoot to Kill. The poster design for both versions are exactly the same; I chose this one purely for the quality of the digital file. If you’ve seen it under either title, it’s a dog of a movie, but I’ve included it because of the incredibly powerful image of the hoodlum that dominates the poster. Surprisingly, this really stands alone in terms of this kind of treatment of the large male figure carrying the weight of the design. There’s another poster coming later in the countdown for a film that is much more well-known than this one, but the mood of the figure in that poster lacks the ferocity and menace of the one here. The combination of the great figurative illustration and the colorful gothic typography makes this one a no-brainer. Note: designers use the word ‘gothic’ to describe tall, condensed, sans-serif letters—I realize everyone else in the world uses the term differently!

42. The Guilty (1942)

42. The Guilty (1942)

Then we have the poster for 1942’s The Guilty, another Poverty Row production, this time from Monogram. Unlike the ambiguity of the image for Murder, My Sweet, this poster is unmistakably film noir. What I love about it is how, despite the use of color photography, the image ‘feels’ black and white, if you get my drift. The shadows … the clothing … the way the man clutches the woman … the title of the film itself: all are indicative of the public’s conception of film noir, and for that matter, mine as well. A wonderfully evocative image, I won’t even get started about my feelings for Bonita Granville—we’d be here all day.

41. Finger Man (1955)

41. Finger Man (1955)

One of my favorite poster designs, especially after I cleaned and brightened this one up! The film noir tropes of alienation and persecution are front and center here, as the anonymous figure in the center of the design points the accusatory finger at the EGR lookalike on the right. The man stands in a visual representation of a spiral, meaning he is about to be swept inescapably into some sort of vortex—the downward descent that almost always characterizes the noir hero’s journey. The bottom of the poster isn’t as exciting, in spite of promising the sex and violence audiences were avidly looking for.

The decision to place the film title in the center of the design is quite novel, splitting the central figure and consequently uniting the poster’s two halves, with the rest of the text sitting comfortably at the composition’s right edge. I wish that so many of these great film poster designs didn’t rely so heavily on fields of yellow—I’d love to see this in red with yellow text instead. Still a first-rate, highly original poster by any measure.

40. The Turning Point (1952)

40. The Turning Point (1952)

Here’s a poster that is as wonderful as it is unusual. In spite of everything that’s going on, the poster feels remarkably simple, boasting an “L” shaped composition that reminds us of the design for Brute Force. Almost everything happening in the here is super, but the vivid color palette and the ingenious title typography (and the way in which the little cops and robbers are putting it to use) is amazing.

When we look down into the “L” shape, I’m impressed by the control and the tight spacing, especially in the handling of the white text, and the placement of the three heads. Pay close attention to the watercolor wash that seems to form the background of the “L” shape; notice how it perfectly holds all of the text, but gets looser and looser and it goes behind the heads, almost until it wafts around them like so much smoke. The female figure in the chair (Sharon Stone, anyone?) is the only photographic element, but by using the yellow overlay the designer has given the photo an illustrated feel that keeps in tune with the rest of the artwork, and, through the use of color, connects the top of the poster to the bottom. Now look away from the poster and ask yourself if you realized that the chair she sits in is a drawing?

The only thing I don’t like here is the yellow color field in the upper corner. I understand why the designer felt it needed to be there, but it wasn’t executed with the same degree of control as the rest of the artwork and sticks out like a sore thumb. This is a poster of rigid horizontals and verticals contrasted with the diagonal forms of the title type—there’s just no place in the composition for that haphazardly applied yellow blob.

39. The Lady from Shanghai (1947)

39. The Lady from Shanghai (1947)

Ah, Rita. We were all wondering when you’d finally show up.

Here’s Ms. Hayworth as one of film noir’s better femme fatales. I don’t mean to channel Coco Chanel, but I love the lines of this poster. It would actually be easy to dismiss this as pure glamour—but the marriage of that tagline with that image is impossible to ignore. Once we read it, it becomes impossible to interpret the image as anything short of menacing. And yet, only after coming to grips with the tagline do we also notice that the woman is positioned against a scarlet background. Very sexy, very subversive, very subtle.

38. Born to Kill (1947)

38. Born to Kill (1947)