Most people believe Alan Ladd

committed suicide, but the details surrounding his 1964 death are so convoluted

no one can be sure what really happened. History is often guilty of erring on

the side of sensationalism—but in Ladd’s case suicide is a reasonable

assumption. Just two years before, in 1962, he was discovered at home, lying

half-dead in a pool of blood, a bullet lodged in his chest. The newspapers and

fan mags bought into the story of an accident, but everyone who knew Ladd believed

that he’d botched a suicide attempt. It really doesn’t matter whether his

January 1964 death was intentional or not—Ladd’s life had been spiraling

downward for years, perhaps even from the moment he broke into the movie

business. It was apparent to anyone paying attention that he was hell-bent on

digging an early grave.

The average movie goer doesn’t understand how arduous life could be for the

stars of studio-era Hollywood, or how truthful that old industry adage: “you’re

only as good as your last picture” really was. It’s a dollars-and-cents, bottom

line, what-have-you-done-for-me-lately kind of racket, and despite a product

that was usually lighthearted, uplifting, and sentimental, the industry itself

could be painfully harsh. It goes without saying that Hollywood dreamers had to

be made of tough stuff, but as is often the case in life, many of those who

struggled mightily to achieve success were bewildered once they actually made

it—and surely didn’t know what to do after the spotlight left them for the next

big thing. Certainly this was the case with Alan Ladd, a hardscrabble kid who

worked a million crap jobs before he finally made it, then was so terrified of

losing it all that he let his insecurities devour him. The foundation upon

which Ladd’s self-esteem stood was simply not strong enough to sustain him. His

fame and wealth notwithstanding, he was the most insecure, frightened, and

guilt-ridden superstar in Hollywood.

Few performers ever made as

smashing a debut as Ladd did in the 1942 film This Gun for Hire, if it can be called a debut at all. Devotees

know This Gun wasn’t

his first appearance. The misconception exists owing to the “and

introducing Alan Ladd as Raven” treatment he gets in the opening credits.

Ladd had been getting bit parts in studio pictures since the mid-1930s, and he

had already scored small gigs in Citizen

Kane, as well as 1942’s Joan

of Paris before his unforgettable breakout in This Gun for Hire. When the first rushes

came in, This Gun director

Frank Tuttle and Paramount execs realized they had lightning in a bottle, and

reworked numerous shots to build him up, bolstering Ladd’s scenes with

Veronica Lake while shifting the focus away from top-billed Robert

Preston. The screen persona that Ladd establishes in This Gun for Hire’s very first scene is one that he would riff on

for more than a decade. It would carry him to the peak of Mount Hollywood, and

make him, for a short while, the most popular screen actor in the world.

Ladd emerged from This Gun for Hire as

a bona fide movie marvel, Paramount’s incandescent star—bigger even than Bing

Crosby. The studio hurried to craft an image that would ensure the public’s

continued adoration. The newly-minted Alan Ladd would be featured

primarily in romantic hero roles. He’d still be tough as nails, but his days

playing hired killers were over. Consequently, Adolph Zuckor felt it

was important to give Ladd a fantastical, picture postcard life story. He was

provided with a studio-written script to use for press interviews and public

appearances, while certain aspects of his past, such as the brief first

marriage and resulting child, were swept under the rug. Ladd would need to

present himself as the smiling family man beginning to dominate the covers of

fan magazines. The sanitized version of his life story presented in Screen Romances and Movie Story wasn’t an outright lie,

but it was a lot for an insecure young actor, uncomfortable with success, to

try to live up to.

Ladd was kind and good-natured,

but horribly apprehensive about his size, his personal history, and, most of

all, his acting. His costars often found him unapproachably distant, though

those he worked with more than once came to realize he was simply terrified

that people would think he was a fraud. Ladd ignored praise, but took to heart

every negative thing written about him. When Geraldine Fitzgerald encouraged

him to accept the lead in The Great

Gatsby he confided, “I won’t be able to do it because I can’t act, you

know.” Yet Robert Preston said, “…he was an awfully good actor. So many people

didn’t realize this. It’s said that the publicity department invented him, but

they didn’t really have to. He would have made it without that, and I think his

life would have been happier.” Virginia Mayo, who adored him, said it best:

“The whole problem with Alan’s psyche was his inability to remember that he was

a big star. And he was the biggest…. The lack of artistic recognition

affected him, affected him tragically…” Though Veronica Lake, who appeared

alongside Ladd more often than any other actress, and whose sad life in some

ways paralleled his, characterized their time together in surprisingly

professional terms: “both of us were very aloof…. We were a very good match for

one another. It enabled us to work together very easily and without friction or

temperament.” However, all who worked with him sensed a deep sadness in the

man. When an interviewer asked him what he would change about himself if he

could, he famously replied, “Everything.”

Ladd was always more at ease with the crew than he was other performers or

studio executives. He had begun in Hollywood as a laborer and enjoyed being around

those who worked behind the scenes. Yet he was able to form lasting friendships

with a few of his costars in spite of being “aloof,” including Edmond O’Brien,

Lloyd Nolan, and Van Heflin — but most notably William Bendix. The pair

met while costarring in The Glass

Key and would appear together in often. They began auspiciously, after

Bendix accidentally cold-cocked Ladd during a fight scene. Ladd was so taken by

the big man’s concern for his safety that they formed an immediate bond. Their

close friendship was widely publicized — they even purchased homes across

the street from one another. According to Bill’s wife Tess Bendix, things went

astray when Ladd’s wife Sue Carol made an offhand remark about Bendix’s lack of

military service. Stuck in the middle, Ladd was obliged to choose between his

friend and his wife, and it would be a decade before the two would have a

conversation that didn’t involve reading lines on a movie set. Once they

finally reconciled, Ladd would lean heavily on his old friend. Bendix was

constantly out of town during the early sixties, working almost exclusively on

the stage. Tess remembers many late-night phone calls that involved a

despondent Ladd pleading with Bendix to break his contracts and return to

California. Bendix’s heartbreak in the wake of Ladd’s 1964 death was

tremendous, and unfortunately short-lived — suffering from pneumonia, he

would follow his best friend in death before the year was out.

The roots of Ladd’s depression can almost certainly be traced back to his

childhood, which was anything but stable — his father died before his eyes when

he was only four years old. When his mother remarried, the family began a

Joad-like trek west and eventually settled in California. Their itinerant days

cost Ladd a few years in school — and consequently he was not only the

smallest, but also the oldest boy in his year. Nor did it help that he made

poor grades, was excruciatingly shy, and had no stable male role model. If

suicide is hereditary, then he never had a chance. In 1937, wrecked on alcohol

and poverty, his mother swallowed ant poison and died before his eyes, just as

he was struggling to get his first break. The incident naturally devastated

him, and many insiders have speculated that he spent the rest of his life seeking

to replace the doting woman who had been his only source of reassurance and

approval. Sue Carol, ten years his senior, filled some of the void left in his

mother’s wake, and Ladd came to consider the Paramount a surrogate home.

Nonetheless, he was plagued with guilt about his mother for the rest of his

days, and when he left the comfortable surroundings of Paramount his peace of

mind and sense of stability deteriorated even further.

Even in the years after he achieved stardom and financial security, Ladd’s

self-image and the rigors of a public life were a source of distress — he

referred to himself as “the most insecure guy in Hollywood.” He wanted to be

thought of as a serious actor but took to heart the whisperings that he was

more a product of Paramount’s publicity machine than his own ability. He wanted

to try different roles, but Adolph Zuckor considered him too valuable, and

wouldn’t risk damaging his carefully constructed screen persona by giving him

other kinds of parts. Ladd never complained much — he would have felt too

guilty. The studio had given him his start, and after having been poor for so

long he felt deeply indebted; so much so that he played ball with his bosses in

ways that seem perplexing today. For much of his career, he kept his first

marriage and the resulting child, Alan Ladd Jr., a secret from the public. The

fan magazines, as well as Sue Carol herself, were more than happy to go along

with the script. Ladd’s squeaky-clean image sold millions of magazines, and it

did no one any good to rock the boat.

Carol, a former

actress-turned-agent, represented Ladd tirelessly during the period leading up

to This Gun for Hire. Even in

the years after they were married, when her public role shifted to that of wife

and mother, she remained the guiding force behind his career. Everyone from

film historians to family friends has suggested that she did as much to

maintain Ladd’s screen image as the studios, and that while their marriage was

sound (Ladd absolutely refused to remove his wedding ring during production of

his films) she nevertheless contributed to the burden of stardom that so

weighed on her husband’s shoulders. She also contributed greatly to his

happiness by giving him two children. Alana was born in 1943, followed by David

in 1947.

Of his three kids David would

follow most closely in his father’s footsteps. He appeared briefly in Shane, and then won a much larger role

alongside Ladd in 1958’s The Proud

Rebel. David received solid notices for his work — as well as a Golden

Globe for Best Juvenile Actor — and quickly became a sought-after child star.

He worked for two decades as a film and television actor, then transitioned to

a long career as a film executive, and was married to Charlie’s Angels actress Cheryl Ladd for seven years.

The need to protect Alan Ladd’s

image waned with his stardom, and the full story of his first marriage and son

finally became public. Movie fans embraced Laddie with no hint of scandal,

though the guilt the father felt at keeping his son a secret for so long was

debilitating. Alan Ladd Jr. would also enjoy a significant career in the movie

industry, becoming one the most successful executives in Hollywood. His tenure

as president of Twentieth Century Fox saw Young Frankenstein, Star

Wars, and Alien hit

theaters. In 1995 he was awarded the Academy Award for Best Picture as producer

of Braveheart. He continues to

produce quality films — most recently Ben Affleck’s Gone Baby Gone.

Alan Ladd spent a decade at

Paramount following This Gun for

Hire, in a succession of weaker and weaker films that still scored millions

for the studio. By the end of the forties, he was arguably the most popular

actor in the world, regardless of the second-rate material the studio put him

in. Darryl Zanuck called him “the indestructible man,” and fully aware of

Ladd’s reputation as a one trick pony, he longed to get him under contract at

Fox. When Ladd finally left Paramount for big money from another studio, it

wasn’t Zanuck but Jack Warner who placed the winning bid. Warner would quickly

come to regret the deal however, as Ladd, no longer in the comforting embrace

of Paramount, began to flounder. His performances got worse and worse, and even

1953’s Shane — made at

Paramount but released after he and the studio separated — couldn’t

resurrect his career. He got great buzz and Shane was a colossal success, but the studios responded by rushing

every awful Ladd picture they had canned into release in order to cash in —

before long he was back where he started, longing to appear in a decent picture

and wondering where things went wrong. For the rest of the fifties Ladd made

one bad movie after the next. He was hopeful about 1957’s Boy on a Dolphin. Cast next to

rising star Sophia Loren, he was devastated when director Jean Negulesco

favored the statuesque Italian beauty and treated him like an afterthought.

Michael Curtiz helmed 1959’s The Man

in the Net, with Ladd in the title role. He was excited to work with an

A-list director, even if Curtiz had a reputation for being a tyrant. Both were

awful failures; it was clear to all that Ladd’s tenure as an above-the-title

film star was over.

Lacking the meaningful work to

distract him from his thoughts, Ladd became an alcoholic. He couldn’t sleep and

got hooked on Secobarbital. Neither his family, his legacy, nor his tremendous

wealth could undo the damage. He believed he had never been given the chance to

be a real actor and had never been taken seriously as anything other than a

pretty face. His problem was that he believed every bad word the

critics had ever written about him, and it was too late to rewrite history. He

appeared one last time, in 1964’s The

Carpetbaggers, as an aging western star. He got decent notices and there

was talk of a comeback as a character actor, à la Edward G. Robinson, but it

wasn’t to be. The once beautiful lead of such films as Lucky Jordan, Two Years Before the Mast, and The Great Gatsby was simply used up. On January 29, 1964,

eight weeks prior to the release of The

Carpetbaggers, Ladd’s butler discovered his body in his Palm Springs

bedroom. Having mixed liquor and sleeping pills one time too many, his body

finally failed. It’s easy to believe he killed himself, but whether he chose to

end his life that night or not, the more important truth is that some people

are simply not blessed with happiness, despite fame and fortune, and try as

they might their pain is such that it eventually overwhelms them. Nobody in

Hollywood was surprised to learn that Alan Ladd was dead.

Returning to This Gun for Hire after viewing the

full arc of Ladd’s career is jarring: his blonde hair is burned into our

memory, though for his debut Paramount ironically dyed his hair black — a

character named Raven couldn’t possibly be fair-haired. Ladd’s mop had held him

back for years —studios believed dark hair photographed better! Paramount, home

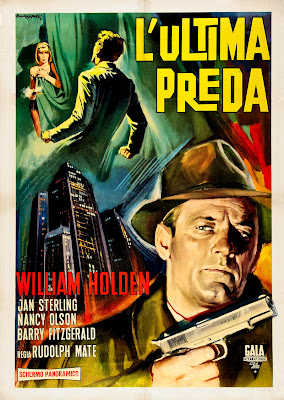

of Sterling Hayden and William Holden, was the only lot where sandy hair wasn’t

considered a setback. However it’s the industry’s never-ending campaign to

camouflage Ladd’s height that we recall now, particularly in This Gun for Hire. Few other actors have

been so stigmatized by their shortness, Ladd especially so because he was a

screen tough guy. Sure, Edward G. Robinson was Little Caesar, but with him size was part of his swagger, an integral

part of his screen image — and unlike Ladd, Robinson was never a romantic

leading man. In Ladd’s case, everyone wished he were taller. He stood

5’6”, as tall as Cagney and just two measly inches shorter than Bogart. Yet

there was something about his look — his boyishness, the pretty face, thin

frame — that made him appear smaller than his older and more famous peers. Like

most small men Ladd was sensitive; he would shy away from making personal

appearances in order to avoid the surprised expressions and hurtful slights of

his those surprised at his size. And while he could occasionally dodge the

public, his stature was an inescapable issue on-set. Robert Preston would write

of their time doing This Gun for

Hire, “…you couldn’t use a stand-in when you were working in a scene with

him because there would be so many cables and stands and reflectors you

couldn’t get in or out. And this is what sort of stultified Laddie. They were

photographing a doll … It’s so sad, because he was an awfully good actor.”

Yet it is to Ladd’s credit that Paramount went to such extremes to give him a

public face, as well as conceal his height — for anyone else they wouldn’t

have bothered. He was the studio’s golden goose; audiences just loved him.

There was no need to purchase a major literary property or shoot on-location,

Ladd’s name on the marquee ensured major profits — even if the picture was a

stinker. Throughout the 1940s his movies were simply bulletproof: every single

one made money, to the tune of $55,000,000 in the studio coffers. No other star

made so much money in such cheap pictures. In the grand scheme of things,

making him look taller was just good business.

Nowhere are the studio’s efforts

to carefully cultivate Ladd’s screen image more apparent than in This Gun for Hire’s opening scene,

which finds his Philip Raven waking from a night of troubled sleep. He sits up

and reaches for an envelope, while palming his nickel-plated automatic. The

camera work is all strictly low angle, and when Ladd finally gets off the bed

his head practically brushes the ceiling. Whether it was the camera position, a

shallow depth of field, or a cut-down set, the shot is obviously contrived to

make Raven appear a great deal taller than Alan Ladd. When that famous

kitten-hating maid shows up, itching for one of the best slaps in movie

history, the camera angle shifts from low to high, and Ladd, now looming over

the girl, is suddenly ten feet tall. This sort of cinematic sleight of hand

would characterize his career. The studios used a number of tricks to make him

appear as tall as possible: he might stand on a raised platform or his leading

lady might step into a freshly dug hole. It’s worth noting that in addition to

their great sexual chemistry, Paramount loved pairing Ladd with Veronica Lake

because she was barely five feet tall — one of the few actresses who could

wear heels and still look right to him.

Although Ladd is more often

described as a movie star rather than an actor (which meant then, as it does

now, that critics credited his success more to his looks than his ability), his

performance in This Gun for Hire is

damn good. The producers knew the film depended casting an actor able to

portray a psychopathic killer who would come across as both cold-blooded and

sympathetic. Ladd was blessed with a face that was chiseled and attractive, and

his knife-edge voice was simply magnificent. His early-career experience as a

radio actor had given him precise control over his pitch and timbre: he could

portray different emotions while keeping his face cold, making Raven one of

noir’s iciest killers. In a few key moments throughout the movie Ladd softens

his character just enough to give the audience a glimpse of the hurt kid

lurking underneath the grim façade. The effect is powerful, and in terms of Hollywood

currency, a star-maker. His special ability to play characters both vulnerable

and tough-as-nails was unique, his special something, the “it” that made him a

magnificent screen star. His physical beauty and potent chemistry with Lake was

the icing on the cake. The Hayes code demanded that Raven pay for his crimes in

the final reel of This Gun for Hire,

but you ache for it not to be so. You wish that he could somehow survive to

escape with the girl, his misdeeds revealed as a frame-up or as a hoax.

Instead, the denouement is clumsy and artificial, with Lake and her putz

boyfriend Preston awkwardly embracing as Ladd bleeds to death at their feet.

The New York critics may have had

Alan Ladd’s number when they derided him as merely a movie star, and

it may also be true that the “serious” career he wanted so badly eluded him.

But in spite of all the criticism and Ladd’s immense self-loathing, his movies

have pleased millions. He made his first splash as a professional killer in an

iconic film noir, establishing a potent new character type that would stand the

test of time and be exploited to the point of cliché in the crime pictures of

the forties and fifties. From trendsetting early efforts such as This Gun for Hire and The Glass Key, through the more

mature The Blue Dahlia, and

even in less well known noirs such as Calcutta, Chicago Deadline, and the

fantastic Appointment with Danger,

Ladd was a key actor in the canon of film noir. His screen charisma, immense

popularity, and ability to humanize the hoodlum ensured the continued

development of the noir style in the Hollywood studio system; and his movies

have weathered the years in ways he couldn’t possibly have imagined. His last

great role came as the good-guy hero in what many consider to be the American

western.

And he thought he was

small.

***

An earlier version of this essay

was published in Noir City, the magazine of the Film Noir Foundation. If the noir

community has a hub, it’s the FNF. My pals over there are working hard to

preserve original 35 mm prints of classic noirs, putting on the fantastic Noir

City film festivals, and publishing a great magazine. Consider clicking the

link and sending ’em a couple bucks. They’ll put it to good use — you’ll become

a real part of film conservation, and get some cool swag too.