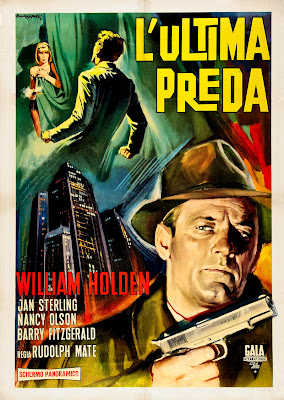

Los Angeles Union Station has been called the “last of the

great railway stations built in the United States.” With its signature clock

tower, tiled arches, and cavernous lobby, the station is one of downtown’s most

recognizable structures. It opened during the summer of 1939, crowding out a

large portion of the city’s Chinatown neighborhood. It has also been a popular

and versatile movie location, appearing in classic noirs such as Criss Cross, Cry Danger, and The

Narrow Margin, as well as in newer films ranging from Bugsy to Blade Runner. However its biggest moment came in 1950, as the

featured location in Paramount’s film noir, Union Station.

Despite the rail connections, Union

Station is essentially a kidnapping picture, peppered with police

procedural elements and suspenseful cat-and-mouse chases. Unfortunately most of

the chatter about the film is mired in the banal issue of where it actually

takes place. With references to New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, the setting

is a geographic impossibility meant, as was en vogue at the time, to be

emblematic of all American cities. It has all of the bells and whistles that

draw us to noir, including a hardboiled story from noir scribe Sydney

Boehm (Side Street and The Big Heat), and a superb visual

identity — courtesy of Rudolph Maté, who transitioned to directing after

earning five Oscar nominations as a cinematographer. Noir fans are most likely

to remember Maté as the director of an earlier 1950 project, D.O.A. — though as unconventional

as the concept of that movie assuredly is, Union Station is in every other way a superior film.

It has a fine cast, with Sunset Blvd.

star William Holden as railroad cop Willie Calhoun, and Oscar

winner Barry Fitzgerald as city police detective Donnelly. The two

actors have great chemistry, and while it has become a cliché for screen cops

to bicker over jurisdiction, their characters work together comfortably.

Regardless of who is actually in charge, the older Donnelly appears content to

mentor his inexperienced protégé rather than taking the lead. Their quarry is

Joe Beacom (Lyle Bettger), a cold-blooded, misogynistic killer who dreamt up a

big time score while doing a stretch for a stick-up. Beacom and a pair of

cronies, Gus and Vince, kidnap Lorna (Allene Roberts), a blind girl who dotes

on her tycoon father, Mr. Murchison (Herbert Heyes). They stash her with

Beacom’s girlfriend (the exceptionally good Jan Sterling, whose part is

entirely too brief) and chase down the commuter train headed for Union Station, where they stow the

girl’s bag and scarf in a locker, then mail the key to her unsuspecting father.

However, Mr. Murchison’s personal secretary Joyce (Nancy Olson), also a

passenger on the train, notices their suspicious behavior and reports her

concerns to the police.

The rail terminal is an ideal setting for the drama of Union Station to play out.

Preceding widespread commercial airline or interstate highway travel, it hosted

the “immense human traffic” of life in the boom years following the Second

World War. Not itself a destination, the terminal is a locus where everyone

hurries, paying as little attention as possible to other travelers. The station

is also a place of many observation points, where police, civilians, and

criminals conduct surveillance. On the whole, Union Station is very concerned with the nuances of how and

what we pay attention to, and with the art of being seen but not noticed. For

those wishing to hide their schemes beneath large-scale comings and goings, the

station is an irresistible venue. And unlike the preening movie gangsters from

a generation before, with their payoffs and ‘legitimate’ businesses, the

heavies of film noir shy away from attention, forcing the police to adopt new

tactics in their fight against crime. Yet like the maze of tunnels that

dominate Union Station’s climax,

something treacherous lurks under the surface of the film: it subtly undermines

the methodology of by-the-book law enforcement, instead arguing for the kind of

gung-ho maverick police officers who would eventually dominate the American

crime film.

The police in movies made prior to Union

Station are typically portrayed as caring family men who live only “To

Protect and Serve,” but the cops here begin to depart from this wholesome

image. Calhoun and his mentor Donnelly want justice for Lorna, but they

cynically believe she’s already dead — and smoothly lie to her father so that

he’ll follow through with the money drop, which they believe will lead them to

the kidnappers. This callous game of charades is all the more chilling as

played by the lovable Fitzgerald, whose character repeatedly promises Mr.

Murchison that the police won’t “do anything” until the money has changed hands

and Lorna is safe.

In Union Station’s one truly

brilliant scene, the police nab Vince, one of Beacom’s accomplices. He refuses

to talk, so a gaggle of cops strong arm him onto the platform and convince him

that he’ll be murdered if he doesn’t snitch. Once again the casting of Barry

Fitzgerald pays off, as he and Holden employ a smooth good cop-bad cop routine

that ends when frustrated good-cop Donnelly mutters to Calhoun, “Make it look

accidental.” Soon Vince’s head is shoved in the path of an oncoming express and

he’s begging to spill his guts. By paying close attention to Holden’s “performance”

during the questioning it becomes clear that the whole thing is a sham; however

it’s fair (and fascinating) to speculate about whether the filmmakers wanted

viewers to take the scene at face value, or as a wink-wink acquiescence to the

Breen Office, which likely would have intervened at any credible evidence that

the cops would stoop to murder. Regardless, the scene showed audiences

something unusual for the time: cops brutally violating a suspect’s civil

rights. The scene evokes a strikingly similar moment in a post-code

contemporary film, L.A. Confidential,

where it’s abundantly clear that while Ed Exley’s slickly polished interrogation

of the Night Owl suspects involves much playacting, Bud White’s actions are

something else entirely.

The irony of Vince’s interrogation is that his capture came not as a result of

police work, but because Joyce, conducting her own surveillance, simply points

him out him to Calhoun. In fact, it is always Joyce, rather than Calhoun or his

men, who identifies bad guys or notices the life-saving detail. Furthermore,

both she and Mr. Muchison make it clear that police involvement in the affair

is not entirely welcome. Joyce expresses regret about reporting her initial

suspicion of Beacom, while Mr. Murchison tells Donnelly that he thinks that

Lorna is most likely to survive if the law stays far away and simply lets him

pay the ransom. Their lack of faith in the cops is understandable but unusual

for a film of this vintage. Although an early scene establishes that Calhoun

can spot a small-time hustler from a mile away, when it comes to heavies like

Beacom the cops are surprisingly ineffective. The kidnappers stroll through the

station without being noticed, even when one them, Gus, is obviously casing Mr.

Murchison. Joyce identifies him, but in the sequence that follows Calhoun can’t

even accomplish a routine surveillance operation. After Gus boards the elevated

train, the police attempt a simple revolving tail, but after they overplay

their nonchalance he gets wise and runs. A footrace quickly gives way to a

gunfight, and Gus meets a grisly fate at the city stockyards. The scene is

exhilarating, but it underlines the recurring notion that the police are out of

their depth. Scratch one kidnapper, but Lorna’s chances of survival are bleaker

than ever. In their defense, the cops understand Beacom better than Mr.

Murchison: Lorna may still be alive, but Beacom has no intention of returning

her to her father. He plans to dump her body in the river as soon as he secures

the ransom.

In light of the law’s many failures, audiences were obliged to decide whether

or not these were just dumb cops — which they do not seem to be — or if the

increased savvy of the hoods and numbers of bodies passing through Union

Station was simply too much to handle. So in this increasingly complicated

world, with its new-type hoods, how can the law expect to stay ahead? The

answer may lie (and pave the way for the movie cops of the next fifty years) in

a fascinating exchange between Calhoun and Donnelly that occurs just after they

receive news that Beacom has gunned down a lone officer pounding a beat:

“That patrolman have a family?"

“Four”

“Too bad he tackled a setup like that alone. A guy doesn’t

jump into the fire feet first.”

“Well, some days a man has to jump. Feet first or head

first.”

“A foolish man.”

“You were in the war, Calhoun. Were you ever pinned down by

mortar fire? In my time it was cannon balls, the kind they have on monuments

now. But even then there was some man, some foolish man who stood up and walked

into it. That’s how wars are won.”

“That’s how fellas wind up on slabs before their time.”

In Union Station’s

exciting underground finale, Beacom surfaces to grab the ransom, but his plans

unravel when Joyce (of course) notices his decisive blunder. In the moments

that follow, Calhoun shrugs off his cop pretensions for the simple truth of the

gun, and becomes that “foolish man” who jumps into the fire. He pursues Beacom

through the machine-filled basements of the train station, and down into the

tunnels that spread underneath like worm holes. High on the rough tunnel walls

are wooden signs that read “Caution: Stop-Look-Listen,” and beneath them cop

and crook punctuate the damp blackness with gunfire, until only the lucky one

is left breathing. Further up the tunnel, a sightless girl sobs over the terrifying

uncertainty of the next few moments...

Union Station (1950)

Studio: Paramount Pictures

Directed by Rudolph Maté

Produced by Jules Schermer

Written by Sydney Boehm

Based on a story by Thomas Walsh

Cinematography by Daniel L. Fapp

Art Directed by Hans Dreier and Earl Hedrick

Starring William Holden, Barry Fitzgerald, Nancy Olsen, Lyle Bettger, Jan Sterling, and Allene Roberts

Running time: 81 minutes

Jumpy. Mr. Upstairs. The dame?

Call her Solitaire. With character names as delicious as these, the plot practically becomes secondary. Here it is anyway. The Feds send Mark Reed (Kent Taylor) down Mexico

way to get to the bottom of an elaborate gold smuggling ring. Seems like a gang

of hoods, run by Mr. Upstairs, have blackmailed a university archaeology

professor (Robert Rockwell) into sneaking the gold through customs hidden

inside artifacts from his dig. Reed infiltrates the gang and things unfold

about as you’d expect them to—until a whopper of a surprise at the end almost pushes the movie into film noir territory. (Not quite though.) There’s almost no chance

you’ll track this down and see it, so I don’t mind spoiling: There’s no sunset

to ride off into for agent Reed. Just when you think he’s about the turn the

tables on Mr. Upstairs, the old man uncorks a revolver and ventilates him.

Borrowed from T-Men? Maybe, but

eyebrow-raising nonetheless.

Jumpy. Mr. Upstairs. The dame?

Call her Solitaire. With character names as delicious as these, the plot practically becomes secondary. Here it is anyway. The Feds send Mark Reed (Kent Taylor) down Mexico

way to get to the bottom of an elaborate gold smuggling ring. Seems like a gang

of hoods, run by Mr. Upstairs, have blackmailed a university archaeology

professor (Robert Rockwell) into sneaking the gold through customs hidden

inside artifacts from his dig. Reed infiltrates the gang and things unfold

about as you’d expect them to—until a whopper of a surprise at the end almost pushes the movie into film noir territory. (Not quite though.) There’s almost no chance

you’ll track this down and see it, so I don’t mind spoiling: There’s no sunset

to ride off into for agent Reed. Just when you think he’s about the turn the

tables on Mr. Upstairs, the old man uncorks a revolver and ventilates him.

Borrowed from T-Men? Maybe, but

eyebrow-raising nonetheless.  Star Kent Taylor acted in

Hollywood for five decades, but he’s a forgettable hero. Likeable but bland, he

reprised Chester Morris’s Boston Blackie

character on television for three years in the early 1950s. Dorothy Patrick

actually gets top billing as Solitaire, the is-she-or-ain’t-she-a-bad-girl

nightclub owner. Patrick accounts for most of the film’s verve. She was coming

off a strong showing in the 1949 Oscar heavyweight Come to the Stable, but her career never took off as it should

have. Film noir fans will undoubtedly recognize her as the girl Friday in

1949’s Follow Me Quietly. Bag of

potatoes Robert Rockwell is billed third. He and Eve Arden spun Our Miss Brooks’s into some small

measure of immortality, but then the cast falls into obscurity. All the fourth billed star, Estelita Rodriguez, has

to offer is a pair of songs.

Star Kent Taylor acted in

Hollywood for five decades, but he’s a forgettable hero. Likeable but bland, he

reprised Chester Morris’s Boston Blackie

character on television for three years in the early 1950s. Dorothy Patrick

actually gets top billing as Solitaire, the is-she-or-ain’t-she-a-bad-girl

nightclub owner. Patrick accounts for most of the film’s verve. She was coming

off a strong showing in the 1949 Oscar heavyweight Come to the Stable, but her career never took off as it should

have. Film noir fans will undoubtedly recognize her as the girl Friday in

1949’s Follow Me Quietly. Bag of

potatoes Robert Rockwell is billed third. He and Eve Arden spun Our Miss Brooks’s into some small

measure of immortality, but then the cast falls into obscurity. All the fourth billed star, Estelita Rodriguez, has

to offer is a pair of songs.