Los Angeles Union Station has been called the “last of the

great railway stations built in the United States.” With its signature clock

tower, tiled arches, and cavernous lobby, the station is one of downtown’s most

recognizable structures. It opened during the summer of 1939, crowding out a

large portion of the city’s Chinatown neighborhood. It has also been a popular

and versatile movie location, appearing in classic noirs such as Criss Cross, Cry Danger, and The

Narrow Margin, as well as in newer films ranging from Bugsy to Blade Runner. However its biggest moment came in 1950, as the

featured location in Paramount’s film noir, Union Station.

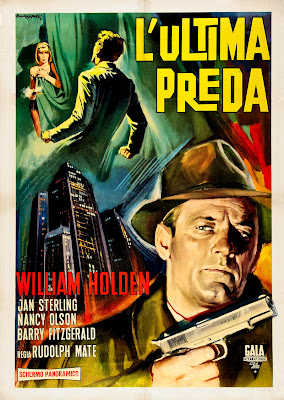

Despite the rail connections, Union Station is essentially a kidnapping picture, peppered with police procedural elements and suspenseful cat-and-mouse chases. Unfortunately most of the chatter about the film is mired in the banal issue of where it actually takes place. With references to New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, the setting is a geographic impossibility meant, as was en vogue at the time, to be emblematic of all American cities. It has all of the bells and whistles that draw us to noir, including a hardboiled story from noir scribe Sydney Boehm (Side Street and The Big Heat), and a superb visual identity — courtesy of Rudolph Maté, who transitioned to directing after earning five Oscar nominations as a cinematographer. Noir fans are most likely to remember Maté as the director of an earlier 1950 project, D.O.A. — though as unconventional as the concept of that movie assuredly is, Union Station is in every other way a superior film.

It has a fine cast, with Sunset Blvd. star William Holden as railroad cop Willie Calhoun, and Oscar winner Barry Fitzgerald as city police detective Donnelly. The two actors have great chemistry, and while it has become a cliché for screen cops to bicker over jurisdiction, their characters work together comfortably. Regardless of who is actually in charge, the older Donnelly appears content to mentor his inexperienced protégé rather than taking the lead. Their quarry is Joe Beacom (Lyle Bettger), a cold-blooded, misogynistic killer who dreamt up a big time score while doing a stretch for a stick-up. Beacom and a pair of cronies, Gus and Vince, kidnap Lorna (Allene Roberts), a blind girl who dotes on her tycoon father, Mr. Murchison (Herbert Heyes). They stash her with Beacom’s girlfriend (the exceptionally good Jan Sterling, whose part is entirely too brief) and chase down the commuter train headed for Union Station, where they stow the girl’s bag and scarf in a locker, then mail the key to her unsuspecting father. However, Mr. Murchison’s personal secretary Joyce (Nancy Olson), also a passenger on the train, notices their suspicious behavior and reports her concerns to the police.

The rail terminal is an ideal setting for the drama of Union Station to play out. Preceding widespread commercial airline or interstate highway travel, it hosted the “immense human traffic” of life in the boom years following the Second World War. Not itself a destination, the terminal is a locus where everyone hurries, paying as little attention as possible to other travelers. The station is also a place of many observation points, where police, civilians, and criminals conduct surveillance. On the whole, Union Station is very concerned with the nuances of how and what we pay attention to, and with the art of being seen but not noticed. For those wishing to hide their schemes beneath large-scale comings and goings, the station is an irresistible venue. And unlike the preening movie gangsters from a generation before, with their payoffs and ‘legitimate’ businesses, the heavies of film noir shy away from attention, forcing the police to adopt new tactics in their fight against crime. Yet like the maze of tunnels that dominate Union Station’s climax, something treacherous lurks under the surface of the film: it subtly undermines the methodology of by-the-book law enforcement, instead arguing for the kind of gung-ho maverick police officers who would eventually dominate the American crime film.

The police in movies made prior to Union Station are typically portrayed as caring family men who live only “To Protect and Serve,” but the cops here begin to depart from this wholesome image. Calhoun and his mentor Donnelly want justice for Lorna, but they cynically believe she’s already dead — and smoothly lie to her father so that he’ll follow through with the money drop, which they believe will lead them to the kidnappers. This callous game of charades is all the more chilling as played by the lovable Fitzgerald, whose character repeatedly promises Mr. Murchison that the police won’t “do anything” until the money has changed hands and Lorna is safe.

In Union Station’s one truly brilliant scene, the police nab Vince, one of Beacom’s accomplices. He refuses to talk, so a gaggle of cops strong arm him onto the platform and convince him that he’ll be murdered if he doesn’t snitch. Once again the casting of Barry Fitzgerald pays off, as he and Holden employ a smooth good cop-bad cop routine that ends when frustrated good-cop Donnelly mutters to Calhoun, “Make it look accidental.” Soon Vince’s head is shoved in the path of an oncoming express and he’s begging to spill his guts. By paying close attention to Holden’s “performance” during the questioning it becomes clear that the whole thing is a sham; however it’s fair (and fascinating) to speculate about whether the filmmakers wanted viewers to take the scene at face value, or as a wink-wink acquiescence to the Breen Office, which likely would have intervened at any credible evidence that the cops would stoop to murder. Regardless, the scene showed audiences something unusual for the time: cops brutally violating a suspect’s civil rights. The scene evokes a strikingly similar moment in a post-code contemporary film, L.A. Confidential, where it’s abundantly clear that while Ed Exley’s slickly polished interrogation of the Night Owl suspects involves much playacting, Bud White’s actions are something else entirely.

The irony of Vince’s interrogation is that his capture came not as a result of police work, but because Joyce, conducting her own surveillance, simply points him out him to Calhoun. In fact, it is always Joyce, rather than Calhoun or his men, who identifies bad guys or notices the life-saving detail. Furthermore, both she and Mr. Muchison make it clear that police involvement in the affair is not entirely welcome. Joyce expresses regret about reporting her initial suspicion of Beacom, while Mr. Murchison tells Donnelly that he thinks that Lorna is most likely to survive if the law stays far away and simply lets him pay the ransom. Their lack of faith in the cops is understandable but unusual for a film of this vintage. Although an early scene establishes that Calhoun can spot a small-time hustler from a mile away, when it comes to heavies like Beacom the cops are surprisingly ineffective. The kidnappers stroll through the station without being noticed, even when one them, Gus, is obviously casing Mr. Murchison. Joyce identifies him, but in the sequence that follows Calhoun can’t even accomplish a routine surveillance operation. After Gus boards the elevated train, the police attempt a simple revolving tail, but after they overplay their nonchalance he gets wise and runs. A footrace quickly gives way to a gunfight, and Gus meets a grisly fate at the city stockyards. The scene is exhilarating, but it underlines the recurring notion that the police are out of their depth. Scratch one kidnapper, but Lorna’s chances of survival are bleaker than ever. In their defense, the cops understand Beacom better than Mr. Murchison: Lorna may still be alive, but Beacom has no intention of returning her to her father. He plans to dump her body in the river as soon as he secures the ransom.

In light of the law’s many failures, audiences were obliged to decide whether or not these were just dumb cops — which they do not seem to be — or if the increased savvy of the hoods and numbers of bodies passing through Union Station was simply too much to handle. So in this increasingly complicated world, with its new-type hoods, how can the law expect to stay ahead? The answer may lie (and pave the way for the movie cops of the next fifty years) in a fascinating exchange between Calhoun and Donnelly that occurs just after they receive news that Beacom has gunned down a lone officer pounding a beat:

“That patrolman have a family?"

“Four”

“Too bad he tackled a setup like that alone. A guy doesn’t jump into the fire feet first.”

“Well, some days a man has to jump. Feet first or head first.”

“A foolish man.”

“You were in the war, Calhoun. Were you ever pinned down by mortar fire? In my time it was cannon balls, the kind they have on monuments now. But even then there was some man, some foolish man who stood up and walked into it. That’s how wars are won.”

“That’s how fellas wind up on slabs before their time.”

In Union Station’s

exciting underground finale, Beacom surfaces to grab the ransom, but his plans

unravel when Joyce (of course) notices his decisive blunder. In the moments

that follow, Calhoun shrugs off his cop pretensions for the simple truth of the

gun, and becomes that “foolish man” who jumps into the fire. He pursues Beacom

through the machine-filled basements of the train station, and down into the

tunnels that spread underneath like worm holes. High on the rough tunnel walls

are wooden signs that read “Caution: Stop-Look-Listen,” and beneath them cop

and crook punctuate the damp blackness with gunfire, until only the lucky one

is left breathing. Further up the tunnel, a sightless girl sobs over the terrifying

uncertainty of the next few moments...

Union Station (1950)

Studio: Paramount Pictures

Directed by Rudolph Maté

Produced by Jules Schermer

Written by Sydney Boehm

Based on a story by Thomas Walsh

Cinematography by Daniel L. Fapp

Art Directed by Hans Dreier and Earl Hedrick

Starring William Holden, Barry Fitzgerald, Nancy Olsen, Lyle Bettger, Jan Sterling, and Allene Roberts

Running time: 81 minutes

Union Station (1950)

Studio: Paramount Pictures

Directed by Rudolph Maté

Produced by Jules Schermer

Written by Sydney Boehm

Based on a story by Thomas Walsh

Cinematography by Daniel L. Fapp

Art Directed by Hans Dreier and Earl Hedrick

Starring William Holden, Barry Fitzgerald, Nancy Olsen, Lyle Bettger, Jan Sterling, and Allene Roberts

Running time: 81 minutes

Karl - Thanks so much for the comments! I certainly can't argue with you about D.O.A., I know I'm in the minority (maybe by myself!) in thinking Union Station is better.

ReplyDeleteYou raise an interesting point about Holden's bona fides as a cop though. Considering that that film tells us that — like most of his peers — Calhoun was a combat vet, he has a certain amount of instant credibility as a tough guy. Yet this also has to be compounded by the disillusionment (and maybe even the need to compensate) that such a man would have felt at being a mere railroad cop. One of the issues that noir tackles regularly is the inability of vets to properly rejoin American society — now I'm wishing I had dug a little more deeply into this with Calhoun. There may have been some interesting comparisons between him and Beacom in that regard.

Barry Fitzgerald captures the working class Irish Catholic ethos perfectly. During a tense moment, he suggests attending a midnight mass. His character has seen it all but still maintains a moral code even though the means are a bit rough.

ReplyDeleteSTL- You got it, if I remember correctly that moment comes in the scene I quote from above — the cocktail scene. It's really great stuff. But then again, there aren't many films that Fitzgerald doesn't greatly enhance with his presence.

DeleteI saw this film in some college festival and never forgot it. The incredible scene where the cops dangle the sidekick into the path of a train, with Barry Fitzgerald shrugging his shoulders, "I tried to help ya... you wouldn't talk though... so... make it quick, boys. Make it look like an accident."

ReplyDeleteBut this is another film of Good & Evil where the Badness of the Bad Guy gives this film an even higher value. Lee Marvin does this is his Bad Guy roles (LIBERTY VALANCE, THE BIG HEAT to name a couple) and here, it's Lyle Bettger delivering a Bad Guy merrily shooting anyone in the back, and kicks them back onto the sidewalk. (I'd also put Ross "I'm NOT Artemus Gordon!") Martin for his EXPERIMENT IN TERROR performance, too.)

Great comment Buffalo Chuck, I agree with you wholeheartedly about Lee Marvin too. Thanks!

DeleteRegarding Karl's comment and Mark's reply, Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson were both railroad cops for part of their (admittedly short) law enforcement careers. You remember the scene in BUTCH CASSIDY & THE SUDNANCE KID where Newman and Redford keep looking over their shoulders at that posse that just keeps on a-comin' and ask, "Who are those guys?" Well, in real life, "those guys" were railroad cops. The guys who solved the Siskiyou Train Robbery in the '20's (re-enacted in the opening minutes of WHITE HEAT) were railroad cops. About 200 of the names on the wall of the National Law Enforcement Memorial in DC belong to railroad cops. Railroad cops still deal with burglars, armed robbers, drug traffickers, interstate fugitives, sexual predators, as well as a hell of a lot of bums, panhandlers, pickpockets. I personally have never had to deal with the psychopathic kidnapper of a pretty, teen-aged blind girl, but who knows?

ReplyDeleteThere's even an organized crime group that provides railroad cops with a "bad guy" mirror image, the Freight Train Riders Association (which is a loosely organized criminal outfit despite its innocuous name).

Railroad cops don't have to prove their bona fides as "real cops." They are real cops. So maybe you should get the facts before you go casting aspersions.

BTW, the source novel for UNION STATION, set more explicitly at NYC's Grand Central Station, the Edgar-winning NIGHTMARE IN MANHATTAN, is also a corker, and the part of Inspector Donnelly reads like it was written for Barry Fitzgerald.

JIM DOHERTY

Sergeant, Railroad Police

Technical Advisor, DICK TRACY comic strip (when are you going to profle the RKO Tracy series, Mark?)

Author, JUST THE FACTS - TRUE TALES OF COPS & CRIMINALS